Nikon F100

Version 1.0.3, last modified April 2nd, 2024, with minor corrections and editing for readability.

Overview

performance. reliability. flexibility.

This is the third in my trilogy of reviews of late-model film cameras manufactured by Nikon. The three cameras I cover–the F65, the F80, and, here, the F100–represent the culmination of design, engineering, and manufacturing expertise built by Nikon over four decades since the introduction of the legendary F1 in 1959. Spanning Nikon’s entry level to prosumer market segments, these three cameras share many technologies and features (some of which would later become incorporated into early digital offerings). Though constructed of different materials and ranging in size and weight, the cameras share a common design language and have similar ergonomics and haptics. All of them were discontinued in 2006, approximately three years before I began taking photography seriously as a hobby. The only film camera produced by Nikon after this time was the flagship F6, which may be the finest 35 mm SLR film camera ever made.

The F100 was introduced in 1999 as a stripped-down version of Nikon’s professional camera of the time, the F5. By the time of its discontinuation, the F100 was sold alongside the F6, the F80 and F75 (at the mid-level) and the F65 and F55 (at the entry level) of Nikon’s lineup of autofocus film cameras. According to Nikon marketing materials of the day, the F100 was targeted to “advanced amateurs and professionals who seek an approachable SLR camera that offers superb image quality and performance.” The F100 featured five-zone autofocus (AF) with Subject Tracking and Lock-on capabilities, through-the-lens (TTL) 3D Matrix, centre-weighted, and spot metering, TTL flash metering, exposure compensation, exposure bracketing, multiple exposure capability, auto DX decoding with manual ISO override, self-timer, depth-of-field preview, dioptre adjustment, and a “hot” shoe for use with external Speedlights. The camera did not have a mirror lock-up function. Its vertically travelling, focal plane shutter was capable of speeds ranging from 1/8000 s to 30 s, and bulb. The F100 was capable of shooting at 4.5-5 fps, depending on power supply (see below).

The F100 is a dependable, fully-featured, high performance camera that offers 90% of the functionality of the F6 at a fraction of the cost and remains a sought-after camera among contemporary film shooters. Perhaps because it “looks like a digital camera” it does not have the hipster caché that is so prized among today’s younger photographers, but what it lacks in aesthetic appeal it more than makes up for in capability. The camera’s quick and accurate autofocusing combined with reliable metering and aperture-priority auto-exposure make it the go-to camera for most of my purposes. This is the camera I choose for portraiture, travel and any other situation when I want to be confident of getting it right the first time.

Shown above is the Nikon F100 mounted with a 58 mm f/1.4 Voigtländer Nokton manual focus lens.

In comparison …

The F100 shares much of its DNA with its little brother, the F80. You might be interested to read my review of the latter, too, especially if you’re considering buying one of these cameras.

Construction and Power Supply

The F100 was ruggedly built and weather sealed. Its front body, top, and bottom covers were constructed of magnesium alloy, giving them the rigidity and strength needed to maintain precise alignment and, as a consequence, permitting a smaller and lighter body. Critical areas were covered with tough rubber surfaces textured to provide a secure grip and buffer against impact and harsh environments. The camera featured O-rings to resist the ingress of moisture and dust.

The F100’s shutter charge, film winding, rewinding, and lens drive motors were “coreless,” which meant they could be driven quietly and smoothly with the minimum of electrical power. Nikon claimed reduced vibration and mechanical noise, and improved responsiveness over conventional “cored” motors in these roles. The F100 also boasted a quick-return mirror with reduced bounce.

The F100 was powered by 4 AA-type alkaline or Li-ion batteries in its standard configuration. Alternatively, the optional MS-13 Battery Holder allowed the camera to accept two CR-123A Li-ion batteries, while the MS-12 holder permitted operation with 2 AA batteries. The optional MB-15 Multi-Power High Speed Battery Pack accepted 6 AA alkaline or Li-ion batteries as well as the MN-15 NiMH Battery Unit.

Unlike the F65 and F80, the F100 did not have a built-in Speedlight. The F100 was manufactured in Japan.

Layout

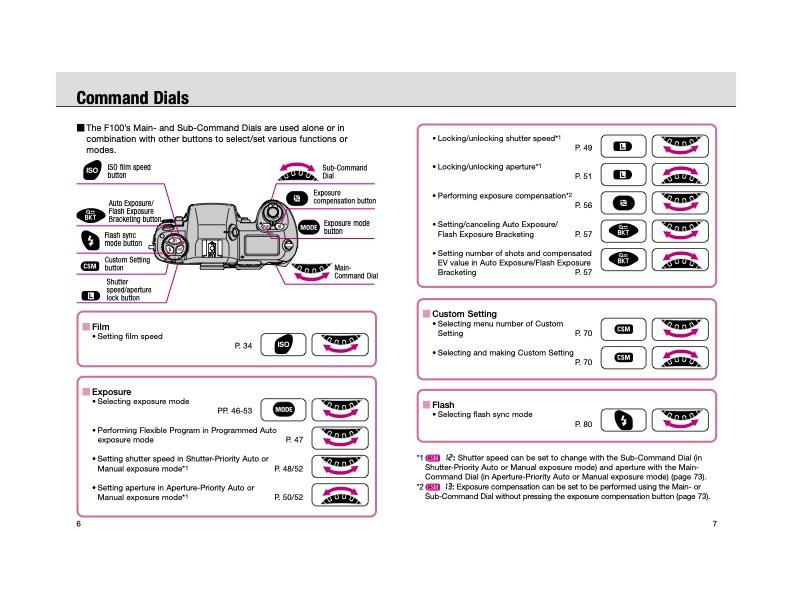

Shown below are pages 2-7 of the user manual, showing the basic configuration of the camera, the information presented in the viewfinder and LCD panel, and the command dials. Click, or tap, to enlarge.

Features

Exposure Modes. Like its smaller sibling the F80, the F100 offered four exposure modes: manual (M), aperture-preferred automatic (A), shutter-preferred automatic (S), and program (P). It likewise lacked fully automatic (AUTO) and “Vari-Program” modes—Portrait, Landscape, Close-up, Sport Continuous, and Night Scene—that were oriented towards beginner photographers and featured prominently on lower model cameras, like the F65.

Unlike the F80, which featured selection of the exposure mode by way of the dial on the camera’s left shoulder, the F100 required the photographer to hold down the “Mode” button on the right-hand side of the camera’s top face (typically using the right index finger) and rotate the rear (“Command”) dial (with the right thumb) to cycle between the four modes. Although it is possible to make these coordinated, single-handed motions without removing your eye from the viewfinder, I have always found it a little awkward because it’s simultaneously necessary to retain a hold on the the right-hand grip of the camera with the remaining three fingers.

Metering Modes. The F100 exposed three possible metering modes to the photographer—Matrix, centre-weighted, and spot—that could be selected by way of a control mounted on the right-hand side of the pentaprism casing on the camera’s crown.

Matrix metering is the branded name that Nikon gave to its computer-enabled evaluative metering system which premiered in Nikon FA, released in 1983 (though in that camera, it was referred to as Automatic Multi-Pattern, or AMP.) This system, which has undergone extensive improvement over the decades since introduction, uses contrast and brightness information originating from multiple “segments” within the viewfinder to feed an algorithm that interprets the scene by comparing it almost instantaneously against an internal database of thousands of “images” in order to select the correct aperture and/or shutter speed, given the selected exposure mode (P, A, or S). When a D-type lens was mounted to the camera, the metering system also took distance information into account. In this case, the metering was properly known as 3D Matrix metering. Like the F80, the F100 featured ten-segment matrix metering (while the F65 had only six). The figure below shows in simplified, diagrammatic form how 3D Matrix metering works.

Nikon’s marketing materials at the time of the F100’s introduction, said the following of the camera’s metering capabilities: “As a pioneer of multi-pattern metering, Nikon designed its Matrix Metering system to read not only scene brightness, but also the “atmosphere” of the scene. It achieves this by analyzing the entire image, while other systems tend to emphasize reading only the segment for the main subject. Moreover: Nikon’s special metering system takes advantage of more than 30,000 scenes from actual shooting experience stored in the F100’s database. Unlike other systems that use algorithms made under simulated laboratory conditions, the F100’s were developed in the field–taking pictures. The F100’s 3D Matrix Meter compares the various scene data in the database with a complex array of actual scene conditions, including brightness, contrast, and selected focus area. The camera’s microcomputer then analyzes the scene using distance information in order to deliver astonishingly accurate automatic exposure control.”

In centre-weighted mode, the F100 favoured properly exposing the centre of the scene (a little smaller than the circle visible in the viewfinder, approximately 13% of the area of the scene) in a 75:25 ratio. This was more heavily weighted in favour of the centre than is typical for Nikon cameras of the past, which usually featured 60:40 metering.

What is metering?

If you’re new to (film) photography, check out my article on the fundamentals of metering.

Focusing. The F100 featured a sophisticated focusing system that presented photographers with a steep learning curve. This system–essentially a complex web of priority-driven behaviours–was built upon three primary focussing modes: manual, Single Servo AF, and Continuous Servo AF, selectable by a physical switch at the 4 pm position of the lens mount on the front of the camera.

For focusing, the F100 relied upon a passive, phase-detection rangefinder called the Nikon Multi-CAM1300. This module was much more capable than the Multi-CAM900, which was built into the F80 and F65, and later into the D70. It featured 5 small sensors that were visible as focal areas, or brackets, arranged in the shape of a cross in the centre of the viewfinder. The central, lefthand, and righthand of these brackets was “cross-hatched,” which meant that they worked equally well with detail aligned vertically and horizontally in the frame. The other 2 (top and bottom) sensors were sensitive unidirectionally, which meant that they sometimes failed to focus if detail in the scene was aligned perpendicularly. Situations that might confuse the Multi-CAM1300 included low-contrast scenes, scenes with objects within the 5 focus zones at different distances from the camera, patterned subjects, and scenes with pronounced differences in brightness within the focus zones. Unlike the F80 and F65, the F100 did not have a built-in AF assist lamp, but it would make use of AF assist in low-light conditions if it were available with a mounted speedlight.

In either of the AF modes, focus was achieved by depressing the shutter release button partway down, or by holding down the “AF-ON” button to the right of the viewfinder at the rear of the camera. When in Single Servo AF mode, also called “focus priority” mode, the F100 focussed once and held focus on that point as long as the release was held partway. It would not fire until focus had been achieved, even if the release were fully depressed. In Continuous Servo AF, by contrast, the F100 would focus continuously as the shutter release was held partway down and fire as soon as the button was fully depressed, whether or not focus had been achieved. This behaviour was called “release priority” because the photographer’s decision to shoot was given precedence over the camera’s ability to focus.

Nikon made much of the F100’s ability to focus on moving subjects. This was a two-fold claim: that the camera was able (1) to adjust focus dynamically in response to a moving subject, an ability called Focus Tracking; and (2) to ignore brief intrusions into the view of another object that temporarily blocked sight of a moving subject, an ability called Lock On. The F100 manual gave the following description of Focus Tracking: “When the focus mode selector is set to Single Servo AF (S) or Continuous Servo AF (C) and the shutter release button is lightly pressed or AF Start button is kept pressed, the camera automatically switches to Focus Tracking when a moving subject is detected. Focus Tracking enables the camera to analyze the speed of the moving subject according to the focus data detected, and to obtain correct focus by anticipating the subject’s position—and driving the lens to that position—at the exact moment of exposure. In Single Servo AF, Focus Tracking is activated with a subject that has been moving in advance [of] the focus detection, and focus is locked when the subject stops moving and [the in-focus indicator] appears in the viewfinder. In Continuous Servo AF, camera continues to track [the] subject (even with a subject which started moving in the middle of the focus detection) and focus is not locked.”

In addition to Single and Continuous Servo AF modes in time, the F100 also featured Single Area and Dynamic Area AF modes in space. The photographer was able to chose between these modes using a lever just to the left of the D-pad on the rear of the camera. When in Single Area AF mode, the F80 used only the focal area currently selected by the photographer to achieve focus. When in Dynamic Area AF mode, by contrast, the F100 began to focus on the subject beneath the currently-selected focal area, but could shift focus, as long as the shutter release were halfway depressed, if the subject were in motion. Under CSM #9 and #10, the photographer was able to control how the F100 responded to “closest-subject priority” while in Dynamic Area AF mode. Closest-subject priority meant that the F100 always selected the focal area with the shortest camera-to-subject distance as the starting point for achieving focus.

The F100’s autofocusing system was excellent, even for moving subjects, and a great improvement over the F80 and the F65, which performed best with stationary and slowly-moving subjects in good lighting. The F100 worked best in AF mode with a compatible lens, but it could also be used in manual focusing mode with older lenses and in situations where the AF system did not work reliably. Under manual focusing, the rangefinder was still active and the camera would indicate accurate focus under the selected focal area by illumination of the in-focus indicator, visible as a green dot at the bottom left of the viewfinder.

I am indebted to technical guru Thom Hogan for everything I know about the auto-focusing systems of late-model Nikon cameras. I have presented briefly here, and in my review of the F80, what he covers in detail in his excellent e-book Thom Hogan’s Complete Guide to the Nikon N80, which I recommend heartily. If there are errors in this section, I claim them exclusively as my own. In my review of the F80, I show a table excerpted from Thom’s guide summarizing the matrix of behaviours created by the temporal and spatial autofocusing modes of the F80. I assume that the F100’s behaviour will be similar, if not identical.

Film-advance Modes. The F100 offered five different film-advance modes. The preferred mode could be selected by rotating the dial at the base of the grouped “bracketing, flash, and ISO” control on the camera’s left shoulder. The selected mode was marked by a white line in the 6 o’clock position. The dial could not be turned without holding down the release button located at the 10 o’clock position. In order of leftmost to rightmost position on the dial, the five modes were:

Multiple exposure: Any desired number of images could be superimposed on the same frame. In this mode, when the shutter release was pressed, the camera cocked the shutter for the next exposure but did not advance the film.

Single advance: One frame for each pressing of the shutter release button.

Continuous advance: 4.5 or 5 frames per second, depending on power supply, for as long as the shutter release button was held down and film remained.

Continuous silent-slow-speed advance: 3 frames per second, quietly, for as long as the shutter release button was held down and film remained.

Self-timer. In this mode, the F100 would not fire until a specified delay of 2, 5, 10, or 20 seconds had elapsed following depression of the shutter release button. During this period, the self-timer indicator LED on the right-hand side of the camera’s front face would blink. The self-timer could be cancelled at any time during the delay by rotating the film advance selector to another mode.

Lens Compatibility. As a testament to Nikon’s technical ingenuity and loyalty to its customers, the F100 was broadly compatible with the majority of Nikkor F-mount lenses, stretching back to the introduction of “automatic maximum-aperture indexing” (AI) lenses in 1977. However, it was designed primarily for use with D-type and AF-S lenses, which communicated with the camera body electronically. When mounted on the F100, the aperture ring of these lenses could optionally be locked at the smallest opening; in this state, working aperture was selected via the sub-command dial on the camera body. This behaviour could be overridden with CSM #22, if the photographer preferred to use the aperture ring on the lens. The F100 focussed AF, D-type, and G-type lenses by way of a screw drive within the camera body while AF-S lenses were focussed by their own internal motors using distance information provided by the camera through electrical contacts at the 12 o’clock position inside the mount.

Older, manual-focus lenses, like the AI-s and AI lenses, could also be used on the F100, though with less functionality. Because the F100 had an AI tab on the lens mount, the camera was able to meter with these lenses (in centre-weighted and spot modes) and made aperture-preferred automatic exposure available to the photographer. This, to me, is the single most compelling reason to buy the F100 over the F80 or F65 (which lacked the AI tab and therefore could not meter with AI-s and AI lenses.) The electronic rangefinder worked properly with these lenses, with confirmation of focus indicated by illumination of the in-focus indicator in the viewfinder.

Aesthetics and Handling

Measuring approximately 155 × 113 × 66 mm and weighing 785 g without batteries, the F100 is noticeably chunkier and heavier than the other cameras that I have reviewed in this series, the F80 and F65. However, it has a substantial right-hand grip which makes it quite easy to carry and its heft contributes to a good sense of balance when the camera is mounted by a long and/or heavy lens. The ergonomics and haptics of the F100 are positive and assured. Its placement of buttons and dials is very well considered. The on-off switch is incorporated into the shutter release; this allows the photographer to activate the camera without taking his eye from the viewfinder. Control of exposure mode, exposure compensation, focus zone, depth-of-field preview, and aperture/shutter speed are also easily achieved (takes practice!) without looking away from the viewfinder. The command and sub-command dials are large, knurled for easy rotation, and have positive, clicky detents, which keep them reliably in the selected position. The camera is rugged, and feels ready for anything.

The viewfinder contains all the essential shooting information illuminated in green text that is easy to read under most lighting conditions. The LCD panel on the camera’s right shoulder is large, information rich, and legible. It is always very easy to tell immediately what “state” the camera is in. The LCD panel can be illuminated by turning the on-off switch to the right.

The camera looks and feels very much like a modern digital SLR.

Pros and Cons

PROS

Although more expensive than the F80, and appreciating, the F100 still represents excellent value for money on the used market. Hard to beat, really.

Excellent ergonomics and haptics; very well considered placement of buttons and dials.

Standard power supply is 4 AA batteries, which are readily and cheaply available.

Rugged and weather-sealed.

Dead simple and reliable film loading, with automatic advancing and rewinding.

Large, informative LCD panel on the camera’s right shoulder and an information-rich viewfinder, with bright, clearly-legible text. This LCD panel can be illuminated for viewing in the dark, which is a very nice touch.

Wide lens compatibility (with caveats), including the ability to meter with AI and AI-s lenses.

Accurate metering, giving perfect exposures every time.

Bright viewfinder with good coverage (96%) and reasonable magnification (0.70x with 50 mm lens set to infinity at -1.0 m-1 dioptre).

Wide range of available accessories, including a data-imprinting back (MF-29) and a battery pack (MB-15) that features a second shutter release button, an “AF-ON” button, and a command dial that make shooting in portrait orientation much easer.

CONS

Lack of a split-ring and micro-prism collar on the focussing screen. This makes it more difficult, though far from impossible, to focus the F100 manually. It is designed to be used primarily in AF mode with fully compatible lenses.

Lack of mirror lock-up and built-in speedlight.

Lack of built-in remote release.

Buying Advice

The F100 was introduced when the camera industry was on the cusp of the transition to digital imaging. It incorporated features that reflected half a century of research and development into 35 mm film photography by the world’s pre-eminent SLR manufacturer. Therefore, it provides excellent value for money on the used market, where it does not fetch the exorbitant prices of older manual-focus cameras that are prized for their retro-cool appearance. I would not hesitate to pick one up, especially if you already own a selection of F-mount glass. I myself am seriously considering buying a second F100 so that I can shoot both colour and black-and-white film simultaneously using the same camera, and so that I have a back-up when one of them eventually fails.

Sample Photos

Other Resources

Other Camera Reviews

Since 2023, I have been working to review all of the cameras that I own and use. This is a large project because my collection contains 25 cameras spanning 5 brands. For a complete list of my cameras and the current status of the project, see Completed and Upcoming Film Camera Reviews. Listed below are the other reviews I have written.

-

The Nikon FM2 enjoyed a production run of almost two decades—and for most of that time, it was an anachronism, even by Nikon’s own standards. When the FM2 was released in 1982, the electronically controlled FE, which included aperture-priority auto-exposure—a feature conspicuous for its absence in the FM2—had already been in production for 4 years; only a year later, Nikon unveiled the “technocamera” or FA, which premiered what came to be known as matrix metering and also incorporated shutter-priority auto-exposure for the first time in a Nikon body; and, at the same time, the company added autofocusing to its flagship camera, in the F3AF model. Until the time the FM2 was finally discontinued in 2001, Nikon continued to iterate its professional line of cameras, including introducing the F4 (1988) and the F5 (1996), while only giving the FM2 a modest upgrade (in 1984, to the FM2N, which featured a new, titanium-bladed shutter and an increased X-sync speed from 1/125 s to 1/250 s). Nikon’s high-end line also underwent an evolution during this period, including introduction of the F90 (1992), F90x (1996), and F100 (1999) series of semi-professional cameras, while the FE was upgraded to the comparatively short-lived FE2 (1983-1987). In its consumer offerings, Nikon experimented across a wide range of cameras with plastic components, new form factors, and electronically-controlled, automatic shooting modes tailored to beginning photographers. And all the while, the venerable, rugged, reliable FM2 looked on, essentially unchanged, inheriting none of these improvements.

-

The F65 was an electronically-controlled, single-lens-reflex, 35 mm film camera introduced by Nikon in 2001. Marketed as the N65 in the United States and the U in Japan, it succeeded the F60 at the low end of Nikon’s autofocus line-up. The F65 included a depth-of-field preview and remote shutter release, which the F60 lacked. The F65 was also available as the F65D variant, which included date-and-time imprinting capability. Offered in both black and silver, the F65 was often bundled with a 28-80 mm f/3.3-5.6G kit lens. Both the body and lens were constructed of polycarbonate plastic and manufactured in Thailand. The camera required two, 3 V CR2 batteries for operation. Nikon offered an optional MB-17 battery grip for the F65, which took 4 AA batteries instead.

-

The F80 was an electronically-controlled, single-lens-reflex, 35 mm film camera introduced by Nikon in January, 2000. Sold as the N80 in the United States, it succeeded the F70 in the mid-range of Nikon’s autofocus line-up, though it appears not to have inherited its design from the camera it replaced. While it resembled the F100 (introduced in 1999 as a stripped-down F5, then Nikon’s flagship professional camera), the F80 was significantly smaller than its big brother and featured a different layout of controls. The F80 lacked the ruggedness and weatherproofing of the F100 and F5, but was comparable in shooting specifications. The camera was offered in three versions: F80, F80D (featuring date-and-time imprinting capability, branded as the N80QD in the US), and F80S (allowing imprinting of exposure information between frames). The two US versions of the camera and the F80S were available only in black. The F80 and F80D were available in black or silver. The body was constructed of polycarbonate plastic and manufactured in Thailand. The camera required two, 3 V CR123A batteries for operation. Nikon offered an optional MB-16 battery grip for the F80, which took 4 AA batteries instead (alkaline, or Li-ion).