Leica R7

Version 1.0.2, June 8th, 2024 (with a link to my review of the Minolta XE and an update on the camera’s condition).

Overview

A Flawed diamond.

The Leica R7 was the last in the line of electromechanical SLR cameras descending from the German-Japanese collaboration that produced the Leica R3 in 1977. That camera, which shared much of its DNA with the Minolta XE (released in 1974 as the XE-1 in Europe and the XE-7 in North America), was the lighter, smaller, and less-expensive-to-manufacture successor to the famously over-engineered and unprofitable Leicaflex SL2 that was produced by Leitz from 1974 to 1976. The partnership between Leitz and Minolta culminated in the release of the R7 in 1992, twenty years after the two companies had signed an agreement of technical cooperation. In 1996, the R7 was succeeded by the R8, which was designed exclusively by Leica and was a radical break from the R3–R7 line.

The Minolta XE

The Minolta XE (1974) is the earliest SLR camera in the line that ultimately produced the Leica R7. It’s a wonderful, inexpensive, picture-making machine.

The R7 was a successor to the R5 (introduced in 1987), rather than to the R6 and R6.2, which were purely mechanical cameras that lacked autoexposure modes. It was the first of Leica’s R-system cameras to be controlled by a microprocessor and to offer variable, through-the-lens (TTL) flash control in automatic program mode. (This makes little difference to me as I seldom use flash and have never used it with the R7, which moreover requires a System Camera Adapter (SCA 351) that I don’t own for proper TTL control.) Though I have never used an R5, the R7 appears to be a modest upgrade, which is in keeping with Leica’s careful, evolutionary approach to introducing new models.

The R7 was a professional camera in both build quality and features. It offered TTL flash metering (in all modes, with appropriate flash and SCA), exposure compensation, auto DX decoding with manual override (6–12,800 ISO), electronic self-timer, viewfinder blind, film canister viewing window, coaxial flash-cable contact, depth-of-field preview, dioptre adjustment, interchangeable viewfinder screens, and a “hot” shoe for use with external flash. Exposure compensation, ISO adjustment, and shooting mode selectors were protected by locks against inadvertent alteration. The camera did not have a mirror lock-up lever, but could be fitted with a mirror release cable. Its metallic, vertically travelling, focal plane shutter was capable of speeds ranging from 1/2000 s to 4 s (set manually) or 16 s (set automatically), and bulb. The maximum flash synchronization speed was 1/100 s.

As one might reasonably expect from any Leica, the build quality of the R7 was excellent. The camera’s chassis was sturdy and heavy. Everything but the rewind crank, which was plasticky and flimsy by comparison, was made to the highest standards. It was available in both all-black and black with chrome trim variants.

The R7 required batteries supplying 6 V. (I use two 1/3N lithium batteries in mine.) An optional MOTOR-WINDER R was available for the R7. It required six AA batteries for operation and provided 2 frames per second. Higher speeds were available using the larger MOTOR-DRIVE R, which required ten AA batteries, and delivered a maximum of 4 frames per second.

(Shown above is the Leica R7 mounted with a 28 mm f/2.8 Elmarit lens and square bayonet hood.)

Layout

The layout of the R7 was fairly conventional. Innovative design features included placement of the release button at the centre of an oversized shutter speed selection dial (reminiscent of the Leicaflex line of cameras) and integration of both the on-off switch and shooting mode selector into this dial. Shown below is page III of the Leica R7 user manual which illustrates the camera’s layout in detail.

Features

Shooting modes. The R7 offered five shooting/exposure modes:

Manual exposure with selective metering, (M)

Aperture-priority auto-exposure with full-field integral metering, [A]

Aperture-priority auto-exposure with selective metering and exposure lock, (A)

Shutter-priority auto-exposure with full-field integral metering, [T]

Program auto-exposure with full-field integral metering, [P]

After my preferred way of shooting, I have typically used the R7 in [A] mode, though I now believe that to be a mistake brought on by my long history of shooting Nikon cameras equipped with nearly infallible “matrix” metering which is vastly superior to Leica’s “integral” metering.

On the topic of full-field integral metering, the R7 manual had this to say: “the full-field integral mode is suitable for all subjects in normal light, with no extremes of light or colour, and where the light and dark areas are fairly evenly distributed over the entire visual field.” This means that full-field integral mode is adequate only when the scene corresponds to an 18% grey field, which is probably not a good representation of most photographs that are worth taking. In the all-too-common situations of uneven lighting, the R7 is best used in (M) or (A) modes, i.e., with selective (read: spot) metering. This makes shooting the R7 much more “manual” than shooting a Nikon camera of similar vintage, which would probably offer a version of “matrix” metering (variously called intelligent or evaluative metering.)

The prototypical “matrix” metering system was introduced to the camera market as Automatic Multi-Pattern (AMP) metering with the release of the Nikon FA in 1983, almost a full decade earlier than the appearance of the Leica R7. Matrix metering uses contrast and brightness information originating from multiple “segments” within the viewfinder, together with lens information, to feed an algorithm that interprets the scene by comparing it almost instantaneously against an internal database of thousands of “images” in order to select the correct aperture and/or shutter speed, given the selected exposure mode (P, A, or S). Full-field integral metering in the R7 is not this! It is much, much dumber and is easily fooled. If you have come to Leica from Nikon, as I did, don’t be fooled by it, as I was. If you are an aperture-priority shooter, as I am, the best way to use the R7 is in (A) mode, i.e., aperture-priority auto-exposure with selective metering and exposure lock. More on this below.

What is metering?

If you’re new to (film) photography, check out my article on the fundamentals of metering.

Viewfinder and focussing. The R7’s viewfinder (shown schematically below) was large and bright. It covered 92% of the frame and had 0.8x magnification. It featured an informative red digital display that was clearly legible in most lighting conditions. The current aperture was conveyed to the viewfinder optically via a small window pointing down towards the lens; in low-light conditions, a supplementary light could be turned on using a switch at the lower left of the mirror housing to illuminate the aperture setting more clearly. The R7 was fitted with a universal focussing screen by default. Like the screens of many other contemporary manufacturers, it featured a central split-ring with microprism collar set into ground glass. This combination made accurate focussing quite straightforward under most conditions.

Key: a–Low light warning (out of exposure metering range). b–Shooting mode. c–Aperture setting (reflected display). d–Fill-in flash. e–Set or calculated shutter speed. f–Light balance in manual mode. g–Calculated aperture in shutter priority mode. h–Warning light for “override activated”. i–Low battery warning. j–Flash ready and flash control. k–measuring circle for selective exposure metering.

Lens Compatibility. The Leica R7 was fully compatible with 3-cam and R-only lenses featuring the Leica R bayonet mount. According to Wikipedia:

The Leica R bayonet mount is a camera lens mount system introduced by Leitz in 1964. The R mount is the standard method of connecting a lens to the Leica R series of 35 mm single-lens reflex cameras. The mount is descended from those used for the Leicaflex, Leicaflex SLand Leicaflex SL2 SLR cameras, but differs in the cams used to communicate lens aperture information to the camera. 3 cam lenses are compatible with all of the Leica SLR cameras, while R-only lenses have a slightly different mount shape that will not fit on the earlier cameras.

The chart below, also taken from Wikipedia, illustrates the compatibility matrix between R-lens types and camera bodies. R-only lenses were deliberately designed by Leica to be incompatible with earlier Leicaflex cameras, and ROM lenses featured contacts for electronic communication between lens and camera.

Prime R-mount lenses are available in focal lengths ranging from wide to telephoto. Generally speaking, their optical performance is superb, as one would expect from Leica glass. Zoom lenses are also available, but these are inferior. Because the 3-cam lenses offer the widest compatibility, they are also the most desirable and command high prices on the used market. Another driver of the increasing prices for these superb lenses is their adaptability to a broad range of digital cameras. They can also be modified (“de-clicked”) for use in video.

Aesthetics and Handling

Like the Nikon FM- and FE-series of cameras, the Leica R7 makes little allowance for ergonomics. Aside from a modest thumb rest on the right-hand side of the camera’s back door, the R7 has no grip to speak of. This minor deficiency is compensated by the solidity and heft of the camera, which conveys a confident, balanced feeling in the hand. Though it is heavy, the R7 positively wants to be picked up.

The R7 has a slotted collar on the take-up spool to make film loading more reliable. I found this to be a little finicky at first, but came to like and appreciate it over time. I am now confident that the film transport system will always engage properly on the first try. I can usually achieve 39 exposures on a 36 exposure roll; autoexposure modes are available even before the frame counter reads “1”. In the Nikon F3, by comparison, autoexposure is not active until the first official frame.

The oversized shutter speed selection dial and integrated shooting mode switch are well placed and give positive haptic feedback. Falling easily to the thumb and index finger of the right hand, they make it quite straightforward for the photographer to operate the camera without taking his eye from the viewfinder.

The shutter speed selection dial doubles as an on-off switch. I have come to prefer this implementation over Nikon’s, which uses the film advance lever to unlock the shutter release and turn on the light meter. When shooting the R7, the film advance lever can remain flush with the camera body while the shutter release button is depressed. In the Nikon FM and FE cameras, by comparison, the lever needs to be in the stand-off position (at a 30 degree angle to the body) for a photo to be taken, which means that it may poke you in the right eye when the camera is held in landscape orientation, or in the forehead when it is held in portrait orientation. It is a welcome relief not to have to deal with this annoyance when using the R7.

Though the construction of the film advance lever feels cheap compared to the rest of the camera, the action is smooth, silent, and satisfying—bested in my opinion only by the Nikon F3, which has the most buttery film advance I have ever experienced. This is the part that Leica gets right about shooting the R7.

The part Leica gets wrong—and it is a major failure—is the sensation of pressing the shutter release button, which is spongy and indefinite. To me, this is the most important aspect of the user experience: every camera manufacturer must get this absolutely right. Pressing the button should spark joy! The button should call out to be pressed again and again. Lamentably, the R7’s does not. For a long time, I was mystified by the hesitance I experienced in the shutter release. It seemed almost as if the button reluctantly traversed two stages on the way to activating the shutter.

I now understand that this is because there are indeed two stages.

The first stage is the meter activation stage: when the button is depressed to this level, the meter turns on and the viewfinder display is illuminated. If the shutter is cocked, the meter and finder remain active for 12 seconds after the button is released. If it is not, they turn off immediately. The second, lower stage is the exposure lock. This applies only when the camera is set to aperture-priority exposure with selective metering, (A). In this mode, the photographer can make a reading from a spot in the scene, depress the shutter release button to the second stage to lock the calculated shutter speed and recompose before pressing the button all the way down to expose the frame. Thus, for the sake of one of five possible metering modes, Leica has compromised the shooting experience by insisting on integrating the exposure lock into the shutter release button. Other cameras dedicate a separate button to AE lock, which is the design I would prefer Leica to have taken with the R7.

Compounding the indefiniteness of the shutter release is the heavy damping of the mirror slap. I fully understand the need to maximize image sharpness by minimizing the vibrations caused my moving the mirror, but the effect of this engineering at the level of the user experience is to make the act of taking a photo seem sluggish, as if the camera lags behind the photographer’s intent. Moreover, the sound the shutter makes is largely independent of speed: all speeds faster than about 1/30 s sound the same. I find this very confusing. On many occasions, it has made me second-guess my settings, or question that the camera is working properly.

The depth-of-field preview lever has a longer travel than I have come to expect from decades of shooting Nikon cameras, and requires much more force to activate (though this may reflect depleted lubrication in my particular body.) I use the DoF preview function quite regularly, and I am always disappointed by Leica’s implementation. Comparative examination of the action of the lever in the Nikon FM3A and R7 demonstrates that the former case is simpler and more direct, while the latter involves rotation of a complex “collar” assembly around the perimeter of the lens mount. (Sadly, this defect has been carried over into the R8, which in every other respect, I find to be superior to the R7.)

Reliability

A question commonly posed on Leica forums regarding the R-series is, “How reliable are these cameras?” The answers are mixed. Some people have experienced decades of faultless service from their bodies, while others complain that the electronic systems integral to the R3–R7 line are prone to failing and, when they inevitably fail, typically cannot be repaired. Having used my R7 for almost two years without any issues, I felt confident that it was reliable. However, while I was writing this review the camera malfunctioned suddenly, without warning, and without any mistreatment. As far as I can tell, it is still working “properly” (i.e., still making correct exposures) but the lower information bar within the viewfinder (displaying exposure mode, shutter speed, and aperture) no longer illuminates when the camera is turned on. This makes it impossible for me to use it in anything other than manual mode, (M). While in this mode, exposure information is still displayed as normal along the right hand edge of the viewfinder, so I can adjust shutter speed and aperture to ensure correct exposure. In all other modes–[A], (A), [T], and (P)–the viewfinder displays no information at all and I cannot tell what shutter speed and/or aperture the camera has set automatically. So, I cannot use any of these modes with confidence. I am now faced with a choice between (i) continuing to use the camera exclusively in manual mode (not my preferred way of shooting when aperture-priority automatic exposure is or should be available); (ii) finding someone qualified to fix it at a reasonable price (assuming parts are available); or (iii) replacing it with another R7 (setting this one aside for future spare parts.)

UPDATE (June 8, 2024): Without any intervention on my part, the digital display in the viewfinder now appears to be working once again. While I am happy about this, it does not inspire me with confidence about the camera’s overall reliability. It is probably just a matter of time before it stops working once more.

Pros and Cons

PROS

Pleasing aesthetics, excellent build quality; good sense of balance in the hand.

On-off switch, shutter release button, and shooting mode selector all integrated into a large, knurled shutter speed selection dial with positive, clicky detents providing great haptic feedback and single-handed operation.

Large, bright viewfinder with good coverage (92%) and reasonable magnification (0.80x with 50 mm lens set to infinity at 0 m-1 dioptre). Excellent information presented in the viewfinder in a legible, non-distracting way.

Wide range of available lenses which have outstanding optical performance.

Reliable film loading system.

CONS

The R7 was the first of Leica’s cameras to be controlled by a microprocessor. Its electronic systems are now 30 years old and are prone to failure.

Although the Leica R7 body may be had at a reasonable price (compared to comparable M bodies, like the M6 and M7), three-cam R lenses are expensive because they are desirable for their outstanding optical performance outside the Leica R ecosystem: they can be adapted to digital cameras of many brands and modified for video. So, they have appreciated on the used market.

Lack of centre-weighted and matrix metering.

Buying Advice

If you want to a comparatively low-cost entry into the Leica brand and aesthetic, the R-system SLR cameras are a good option (particularly if the rangefinder does not agree with you.) However, there are three reasons I cannot wholeheartedly recommend the R7. They are:

The electronics are prone to failure and cannot be repaired.

The R-mount lenses are expensive.

The metering system is less capable than contemporary cameras from other manufacturers.

In addition to these objective reasons, there is also the very subjective reason that the shutter release button and mirror damping make for a shooting experience that is, for me, less than satisfactory.

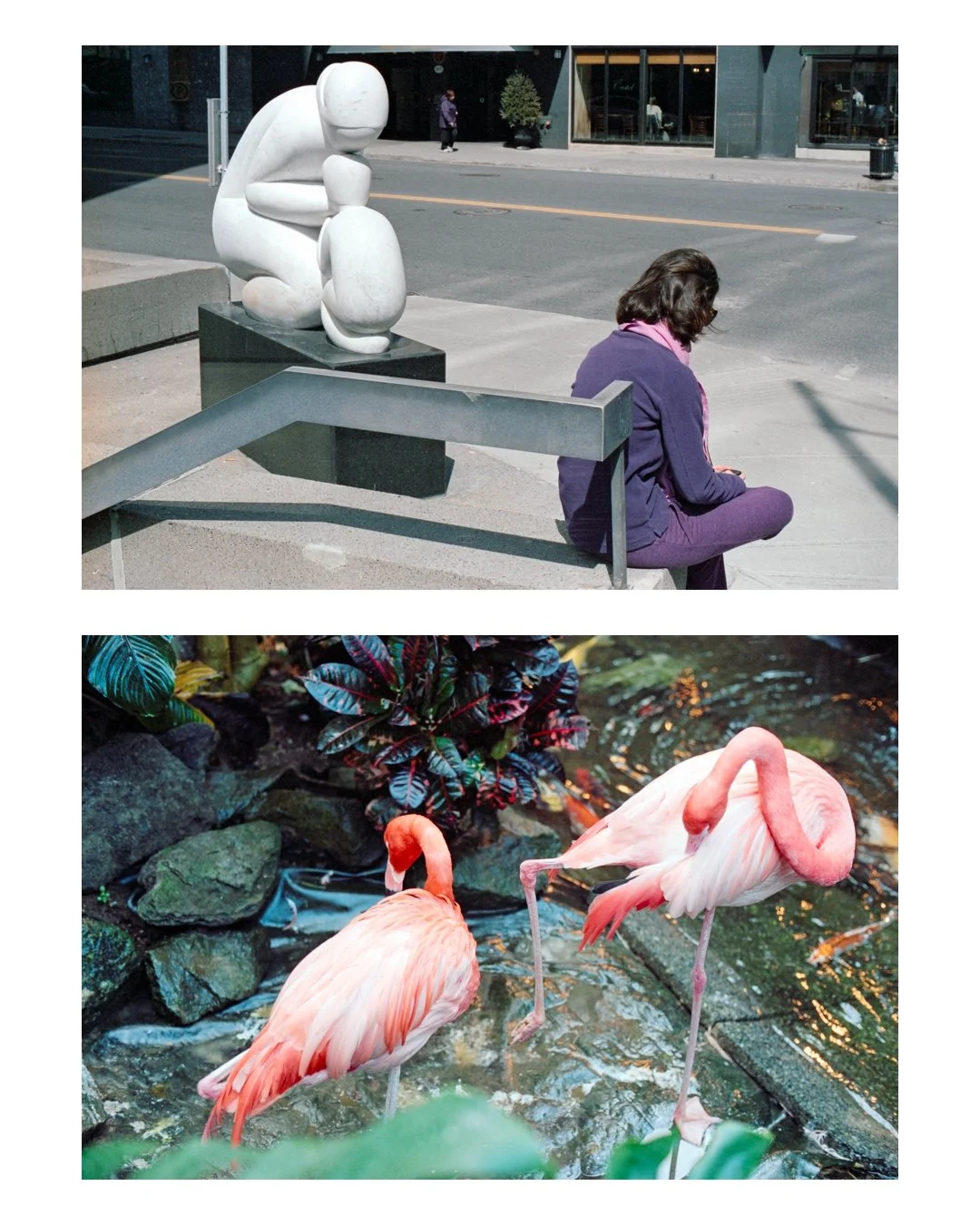

Sample Photos

Other Resources

Other Camera Reviews

Since 2023, I have been working to review all of the cameras that I own and use. This is a large project because my collection contains 25 cameras spanning 5 brands. For a complete list of my cameras and the current status of the project, see Completed and Upcoming Film Camera Reviews. Listed below are the other reviews I have written of manual focus cameras.

-

The EM was an inexpensive, ultra-compact, electromechanical, manual focus, 35 mm SLR camera introduced to international markets by Nippon Kogaku (later Nikon) in 1979. Its Japanese debut came in 1980 simultaneously with the F3. The EM was succeeded in 1982 by the FG.

-

The Nikon FM2 enjoyed a production run of almost two decades—and for most of that time, it was an anachronism, even by Nikon’s own standards. When the FM2 was released in 1982, the electronically controlled FE, which included aperture-priority auto-exposure—a feature conspicuous for its absence in the FM2—had already been in production for 4 years; only a year later, Nikon unveiled the “technocamera” or FA, which premiered what came to be known as matrix metering and also incorporated shutter-priority auto-exposure for the first time in a Nikon body; and, at the same time, the company added autofocusing to its flagship camera, in the F3AF model. Until the time the FM2 was finally discontinued in 2001, Nikon continued to iterate its professional line of cameras, including introducing the F4 (1988) and the F5 (1996), while only giving the FM2 a modest upgrade (in 1984, to the FM2N, which featured a new, titanium-bladed shutter and an increased X-sync speed from 1/125 s to 1/250 s). Nikon’s high-end line also underwent an evolution during this period, including introduction of the F90 (1992), F90x (1996), and F100 (1999) series of semi-professional cameras, while the FE was upgraded to the comparatively short-lived FE2 (1983-1987). In its consumer offerings, Nikon experimented across a wide range of cameras with plastic components, new form factors, and electronically-controlled, automatic shooting modes tailored to beginning photographers. And all the while, the venerable, rugged, reliable FM2 looked on, essentially unchanged, inheriting none of these improvements.