Nikon F65/N65

Version 1.0.3, last modified October 10th, 2023, with minor additions and corrections.

Jump to Section

Please notify me of errors by emailing nathan.d.jones@gmail.com

Overview

The F65 was an electronically-controlled, single-lens-reflex, 35 mm film camera introduced by Nikon in 2001. Marketed as the N65 in the United States and the U in Japan, it succeeded the F60 at the low end of Nikon’s autofocus line-up. The F65 included a depth-of-field preview and remote shutter release, which the F60 lacked. The F65 was also available as the F65D variant, which included date-and-time imprinting capability. Offered in both black and silver, the F65 was often bundled with a 28-80 mm f/3.3-5.6G kit lens (pictured above, in silver.) Both the body and lens were constructed of polycarbonate plastic and manufactured in Thailand. The camera required two, 3 V CR2 batteries for operation. Nikon offered an optional MB-17 battery grip for the F65, which took 4 AA batteries instead.

The F65 was discontinued in 2006. During its production run, it was sold alongside the F55 (at the low end), the F75 (in the mid-range), and the F80 and F100 (at the high-end) of Nikon’s portfolio of consumer-level autofocus cameras. It spanned the transition from the F5 to the F6 in Nikon’s professional line. The F65 competed directly with Canon’s EOS Rebel 2000.

Although it was positioned at the bottom of Nikon’s product line and marketed to beginners, the F65 was a fully-featured camera that included many of the capabilities that professional photographers of the era had come to expect (though not to the same rigorous specifications.) These were autofocus (AF), through-the-lens (TTL) metering, exposure compensation, exposure bracketing, multiple exposures, auto ISO setting, self-timer, depth-of-field preview, dioptre adjustment, and remote release. The camera also sported a built-in flash, called a “Speedlight” by Nikon, and a “hot” shoe. The camera lacked a dedicated mirror lock-up. Its vertically travelling, electronically controlled, focal plane shutter was capable of speeds ranging from 1/2000 s to 30 s, and bulb.

In comparison …

The F65 shares much of its DNA with the F80. You might be interested to read my review of the latter, too, especially if you’re considering buying one of these cameras.

Layout

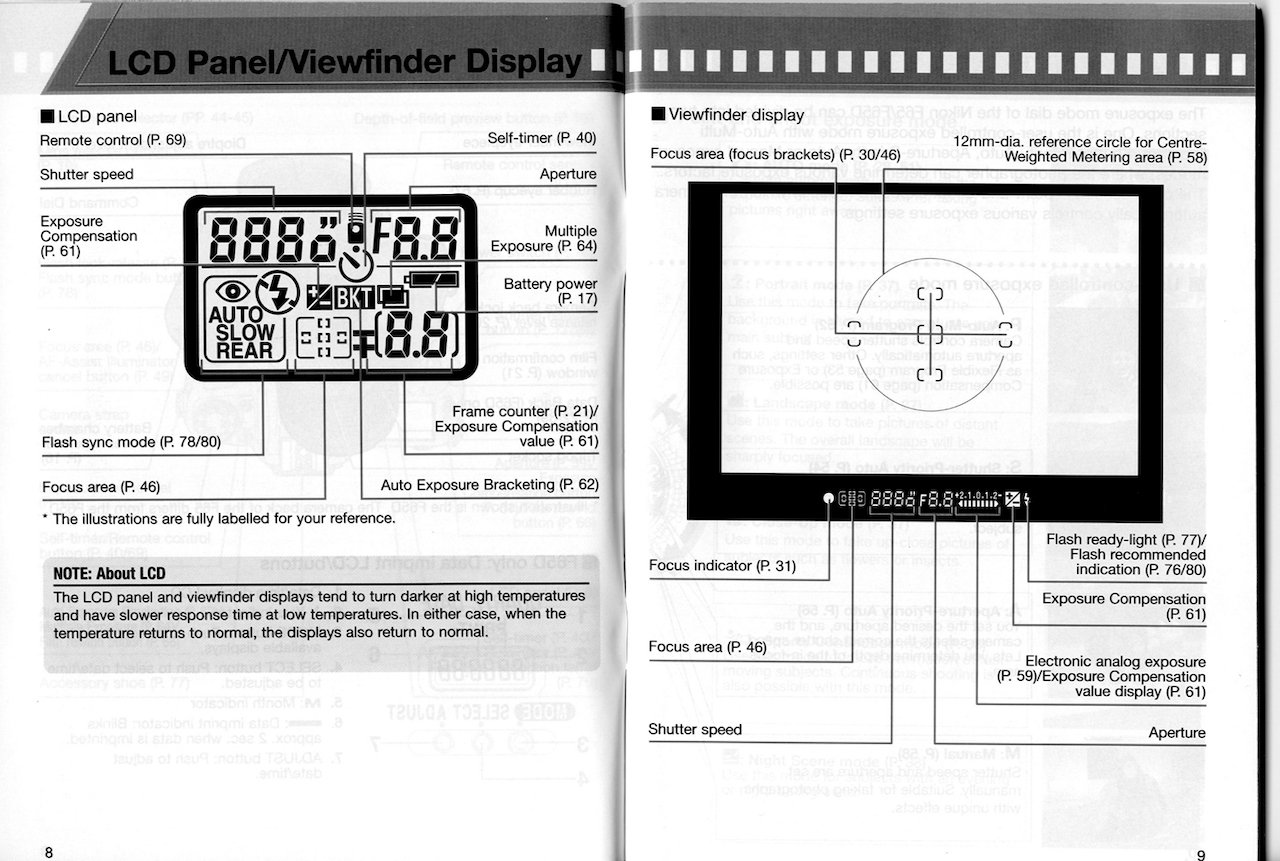

Scanned copies of Pages 6-9 in the Nikon F65 instruction manual, showing the basic layout of the camera, the information displayed in the LCD panel, and the viewfinder display.

Features

Exposure Modes. The F65 offered 10 distinct exposure modes. These included the familiar manual (M), aperture-preferred automatic (A), shutter-preferred automatic (S), and program (P) modes, together with a fully automatic mode (AUTO), which essentially turned the F65 into a point-and-shoot camera. In addition to these, the camera also featured 5 other modes designed to make it easier for beginning photographers to achieve excellent results in a variety of conditions. These “Vari-Program” modes–Portrait, Landscape, Close-up, Sport Continuous, and Night Scene–were groups of pre-defined variables that were automatically set by the camera in anticipation of a specific use case. For example, in Sport mode, which was designed to freeze action, the F65 automatically preferred high shutter speeds, activated continuous AF, and enabled continuous shooting (at 2.5 frames per second, with fresh batteries.)

Lens Compatibility. As a testament to Nikon’s technical ingenuity and loyalty to its customers, the F65 was compatible to a greater or lesser degree with most Nikkor F-mount lenses, stretching back to the introduction of “automatic maximum-aperture indexing” (AI) lenses in 1977. While it was designed primarily for use with G-type (“gelded”) lenses, which lacked an aperture ring, it also worked perfectly with D-type and AF-S lenses, which, like the G-type lenses, communicated with the camera body electronically. When mounted on the F65, D-type lenses had to be set to minimum aperture; in this state, aperture could be changed via the command dial on the camera body, rather than by the aperture ring on the lens. The F65 focussed G- and D-type lenses by way of a screw drive within the camera body, while AF-S lenses were focussed by their own internal motors using distance information provided by the camera through electrical contacts at the 12 o’clock position inside the mount. Older, manual-focus lenses, like the AI-s and AI lenses, could also be used on the F65 in fully manual mode without metering. The electronic rangefinder worked properly with these lenses, with confirmation of focus indicated by illumination of the in-focus indicator in the viewfinder.

Focusing. The F65 could be used in either manual or autofocus modes, selectable by a physical switch at the 4 pm position of the lens mount on the face of the camera. For AF, the camera depended on a phase-detection rangefinder, which was built on the Nikon Multi-CAM900 AF module. To assist the rangefinder in low-light environments, the F65 was equipped with an AF assist lamp. When in AF mode, the F65 automatically switched between Single Servo AF and Continuous Servo AF, depending on whether the subject was still or moving, respectively; if a subject initially at rest began to move after focus was achieved, the camera would deactivate the focus lock and transition to Continuous Servo AF automatically.

The F65 had 5 autofocus zones arranged in the shape of a cross within the central portion of the viewfinder. In AUTO shooting mode, and in any of the Vari-Program modes except Close-Up, the camera defaulted to Dynamic AF Mode with Closest Subject Priority, which meant that it automatically focussed on whichever object in the field was closest to any of the 5 zones. Alternatively, the photographer could select a single zone for the camera to focus on. When a single zone was selected, the F65 automatically moved into Dynamic AF Mode, which meant that it used distance information from the selected zone as well as from those nearby to maintain focus (on a potentially moving subject.)

Regardless of whether the subject was moving, or still, the shutter could only be released when the in-focus indicator was illuminated in the viewfinder. This meant that, when in AF mode, the F65 was incapable of taking photos that were out of focus. It also meant that a shot could be missed altogether (and many were) because the camera was incapable of achieving focus in that particular instance. Situations that were likely to confuse the CAM900 included low-contrast scenes, scenes with objects within the 5 focus zones at different distances from the camera, patterned subjects, and scenes with pronounced differences in brightness within the focus zones.

Metering. In all shooting modes other than manual, the F65 featured six-segment matrix metering. When a G-type, D-type, or AF-S lens was mounted, 3D matrix metering was activated, which meant that the camera took into account distance information in addition to brightness and contrast when determining exposure. In manual mode, the camera automatically switched to 60-40 centre-weighted metering. Without selecting manual mode, the photographer was not able to choose centre-weighted over matrix metering. The F65 did not have a spot metering option.

Aesthetics and Handling

Weighing only 395 g without batteries and measuring approximately 140 x 92 x 66 mm, the F65 is a compact, lightweight camera with fantastic ergonomics. Its placement of buttons and dials is very well considered, and though it is made of inexpensive polycarbonate, the camera has excellent fit and finish and feels good in the hand. The battery compartment doubles as a right-hand grip, which makes it easy to hold, and the on-off switch is incorporated into the shutter release, which allows the photographer to activate the camera without taking his eye from the viewfinder. Control of exposure compensation, focus zone, depth-of-field preview, and aperture/shutter speed are also easily achieved without looking away from the viewfinder by rotation of the command dial (using the right thumb) with or without simultaneously pressing a modifier button. The command and shooting mode selection dials are large, ridged for easy rotation, and have positive, clicky detents, which keep them reliably in the selected position.

The viewfinder contains all the essential shooting information illuminated in green text that is easy to read under most lighting conditions. The LCD panel on the camera’s right shoulder is large, information rich, and legible. It is always very easy to tell immediately what “state” the camera is in.

The F65 breaks from the chunky, aggressive styling of Nikon’s consumer offerings in the late 80s and 90s. The F65 is Luke Skywalker to the F-501’s Darth Vader. It is smaller, less hard-edged, and less elaborated with coloured buttons and dials. Personally, and perhaps for nostalgic reasons, I find the F65’s turn-of-the-century aesthetics to be very pleasing, though I would have preferred my copy in black, rather than silver. The former looks more “professional.”

Pros and Cons

Pros

Compact and lightweight with excellent ergonomics; very well considered placement of buttons and dials.

Though constructed of inexpensive materials, the F65 has excellent fit and finish. It feels well made in the hand.

Pleasing aesthetics.

Dead simple and reliable film loading, with automatic advancing and rewinding.

Large, informative LCD panel on the camera’s right shoulder and an information-rich viewfinder, with bright, clearly-legible text.

Wide lens compatibility (with caveats).

Accurate metering, giving perfect exposures every time.

This is a camera that “grows with you.” Beginning photographers can rely on its AUTO and Vari-Program modes to achieve excellent results, while more experienced shooters can take advantage of its less automated, more professional features.

Cons

Small, dim viewfinder with poor coverage (89 %) and low magnification (0.60–0.68, depending on dioptre setting).

Lack of a split-ring and micro-prism collar on the focussing screen. This, combined with the point above, makes it more difficult to focus the F65 manually.

Reliance on CR2 batteries, which are more expensive and not as widely available as AA. The optional battery grip, which could solve this problem, is expensive and hard to find on the used market.

Lack of metering with older, manual focus lenses.

Inability to switch freely between metering modes.

Weak autofocus capability with pronounced “hunting,” even in moderately lit conditions.

Lack of weather sealing.

Lack of LCD panel backlight.

Lack of dedicated mirror lock-up and eyepiece blind.

Slow top flash sync speed (1/90 s).

Suffers from the “stickiness” that plagues the faux leather of older Nikon gear.

Buying Advice

The F65 was introduced when the camera industry was on the cusp of the transition to digital imaging. It incorporated features that reflected half a century of research and development into 35 mm film photography by the world’s pre-eminent SLR manufacturer. In this context, it provides excellent value for money on the used market, where it can be had routinely for approximately $50 in great condition. That being said, the earliest production models are now over 20 years old and, as is the case for most aging electronic devices, can no longer be repaired when something inevitably goes wrong. My own copy has intermittent problems with autofocusing that I know cannot be remedied; the psychological overhead of worrying about the camera’s unreliability make me less likely to use it. You may have a similar experience with yours. So, there is a degree of risk in buying an F65, but given the camera’s low cost, it may be a risk worth taking if you prefer a compact, lightweight, well-specified camera that you can toss into a bag and take everywhere.