The music of my youth (early 1990s). From L to R, top to bottom: “Achtung Baby” by U2, “Nevermind” by Nirvana, “Angeldust” by Faith No More, “Ritual de lo Habitual” by Jane’s Addiction, “Out of Time” by R.E.M., “August and Everything After” by Counting Crows, “Blind Melon” by Blind Melon, “Gish” by Smashing Pumpkins, and “10” by Pearl Jam.

Software is eating the world. The tide is turning ineluctably towards the virtual, the temporary, the just-in-time, and the disposable. Music fans and casual collectors who bought physical media over the decades are now finding their entertainment needs more than satisfied by the superabundance of streaming services. They are purging their living rooms, basements, and attics of the obstinate reminders of the embarrassingly unrefined musical tastes of their teenage years. As homes are decluttered and renovated, the question arises of what to do with all those CDs (as well as the books and DVDs) which seem to so many to be obsolete relics of a bygone era.

One possible answer to the question is: give them to me. I would be happy to take your used CDs for practical, aesthetic, and philosophical reasons.

Practical Reasons

(1) CDs are inexpensive, durable, and compact. Unlike the venerable LP, which is enjoying a modest renaissance among the cool kids and enjoys prominent display in said living rooms, the humble CD is finding itself packed by the dozen into Amazon boxes and dropped off at the back door of the local thrift store beneath mountains of used clothing, well-loved toys, and other sundries that have received perfunctory Marie Kondo blessings. This unwarranted ignominy is your opportunity. Just today, I bought ten CDs for $5 (including "Desire" by Bob Dylan, "Tupelo Honey" by Van Morrison, "Breakfast in America" by Supertramp, and "Brothers in Arms" by Dire Straits. Do these albums accurately reflect my musical tastes? Not really, but at these prices I can well afford to experiment and challenge my preferences.)

Records are easily scratched and degrade with each playing; CDs are rugged. They are remarkably resistant to the kind of physical damage that would make them unplayable and sound just as good after 20 years of rough use as on the day they were made, even if the playing surface is no longer pristine. They can therefore be purchased second- (or third-) hand with much more confidence than can LPs, which, on the used market, are typically more scratched than I would prefer and tend to play with annoying crackles and pops. Call me reckless, but given thrift store prices, I don't hesitate to buy CDs without checking the quality of the playing surface. The limit of my quality control is to verify that the jewel case actually contains the CD the cover claims it to contain. (Sometimes, cases are empty, which I can usually tell just by the weight of the case in my hand; on other occasions, they contain the "wrong" CD.)

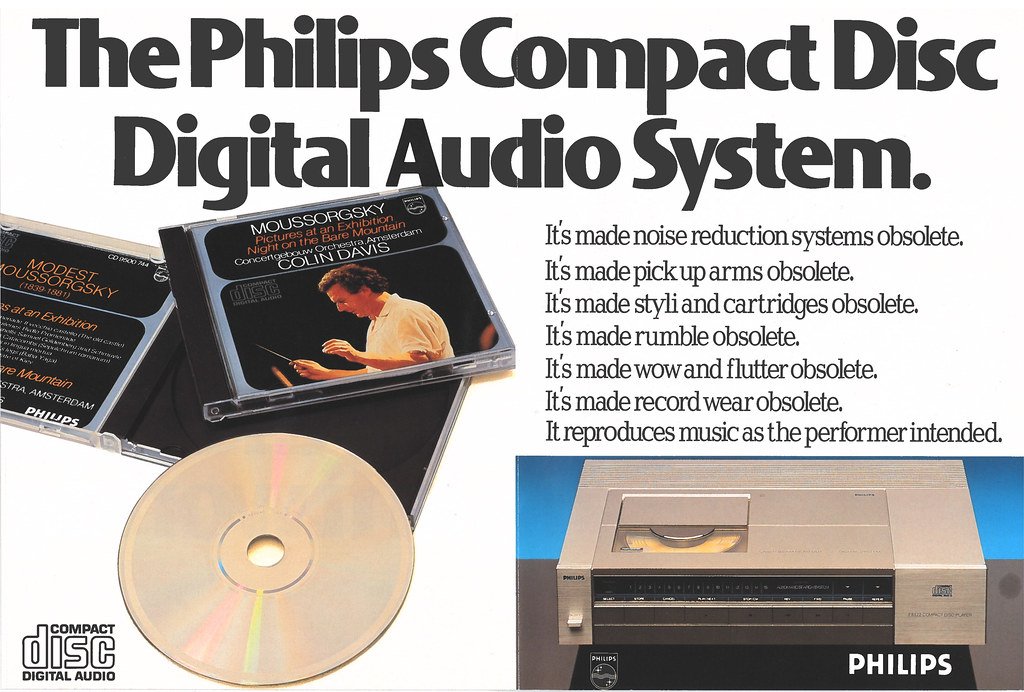

Early print advertising by Philips, one of the co-creators of the compact disc. This advertisement extolling the technical virtues of the new medium appeared in 1982 in “3,” the short-lived magazine of BBC Radio 3.

The CD is much smaller than the LP. With a diameter of only 120 mm, it can be held easily between the fingers of one hand by most adults. (The physical dimensions of the disc were established by Sony, which insisted that the entirety of Beethoven's Ninth Symphony--74 minutes of music--should be accommodated by a single CD. Sony's competitor in the production of the new, digital technology, Philips, had proposed a diameter of only 115 mm, but this was rejected because it would have made the disc too small to contain the Ninth--much to the relief of classical music enthusiasts the world over.) A combination of the standard jewel case and appropriate shelving allows thousands of CDs to stored in a comparatively small space. I say "appropriate shelving" because most book cases have too much vertical space between the shelves to permit efficient storage of CDs, books generally being much taller than jewel cases. This annoying fact complicates storage and necessitates tailored solutions for collectors with large libraries. The problem of where to put all the discs does not disappear just because the CD is physically smaller than the LP; the dimensions of each format demands a bespoke solution. However, with appropriate shelving, more CDs than LPs can be accommodated within the same living room. CDs in a large library can be found, extracted from their cases, and played more easily and quickly than can LPs--and with much less care and fuss over the handling of the discs.

My new old stock JVC audio gear, manufactured in the 1990s. Obscured at bottom right is a Topping D30 “hi-res” DAC, which is connected to the Mac on my desk. Most audiophiles regard this equipment with derision; I have a special fondness for it. Many consider the proliferation of buttons and dials on brushed titanium to be ugly. Once again, I disagree. Nostalgia is a powerful emotion.

(2) CDs (generally) produce sound of very high quality, even on "mid-fi" equipment. I will not touch upon the age-old debate of which sounds "better," CDs, or LPs, because that is predominantly a matter of personal taste; I like, appreciate, and regularly play both. There is no contesting which is "cooler." Vinyl wins that debate easily. That being said, the CD to my ears sounds excellent, provided that the music has been well recorded and produced. It eliminates the annoying crackles and pops that plague vinyl (which some people find charming--I don't.) Music on a CD is digitized using a dynamic range represented by 16 bits, or 65,536 "levels of loudness," and a sampling rate of 44.1 kHz, the so-called "16/44" or "WAV" format. (As a technical aside, the sampling rate was carefully chosen by the original engineers of the CD to ensure that all frequencies audible to the human ear--roughly 20 Hz to 20 kHz--could be captured.) "Hi-res" digital files, which are widely available for purchase as downloads and through subscription streaming services, are encoded at higher bit-depths and sampling rates (e.g., 24/96 and 24/192) and should therefore be better able to reproduce the original sound of performed music, which is "born analog." However, I simply can't tell the difference between CD quality and "hi-res" digital sound, so it doesn't make much sense for me to spend the extra money for the "hi-res" formats (and the new equipment I would need to enjoy it). My inability to differentiate probably owes as much to my middle-aged ears as it does to my modest hi-fi equipment.

Print advertising from 1983 by the other co-creator of the compact disc, Sony.

(3) The catalogue of music readily available in CD format is enormous. When the CD first appeared for sale in the early 1980s, both Sony and Philips mounted aggressive advertising campaigns extolling the vitues of the new format. Record labels stoked demand by encouraging music lovers to duplicate their collections digitally. This meant that they had to reissue their back catalogues on CD as well as begin to release new music in digital format. It was a winning formula. From 1982, CD sales grew rapidly. They peaked in the United States in 2000 on revenues of $13.2 billion, which accounted for 92% of all music sold that year. Though sales have declined precipitously since the glory days of Eminem, N Sync, and Britney Spears, most music released today is still pressed to CD and is available, albeit expensively, from the few remaining brick-and-mortar music shops as well as Amazon and other online retailers. Sometimes CDs are icluded in record sleeves, along with a coupon for a hi-res digital download.

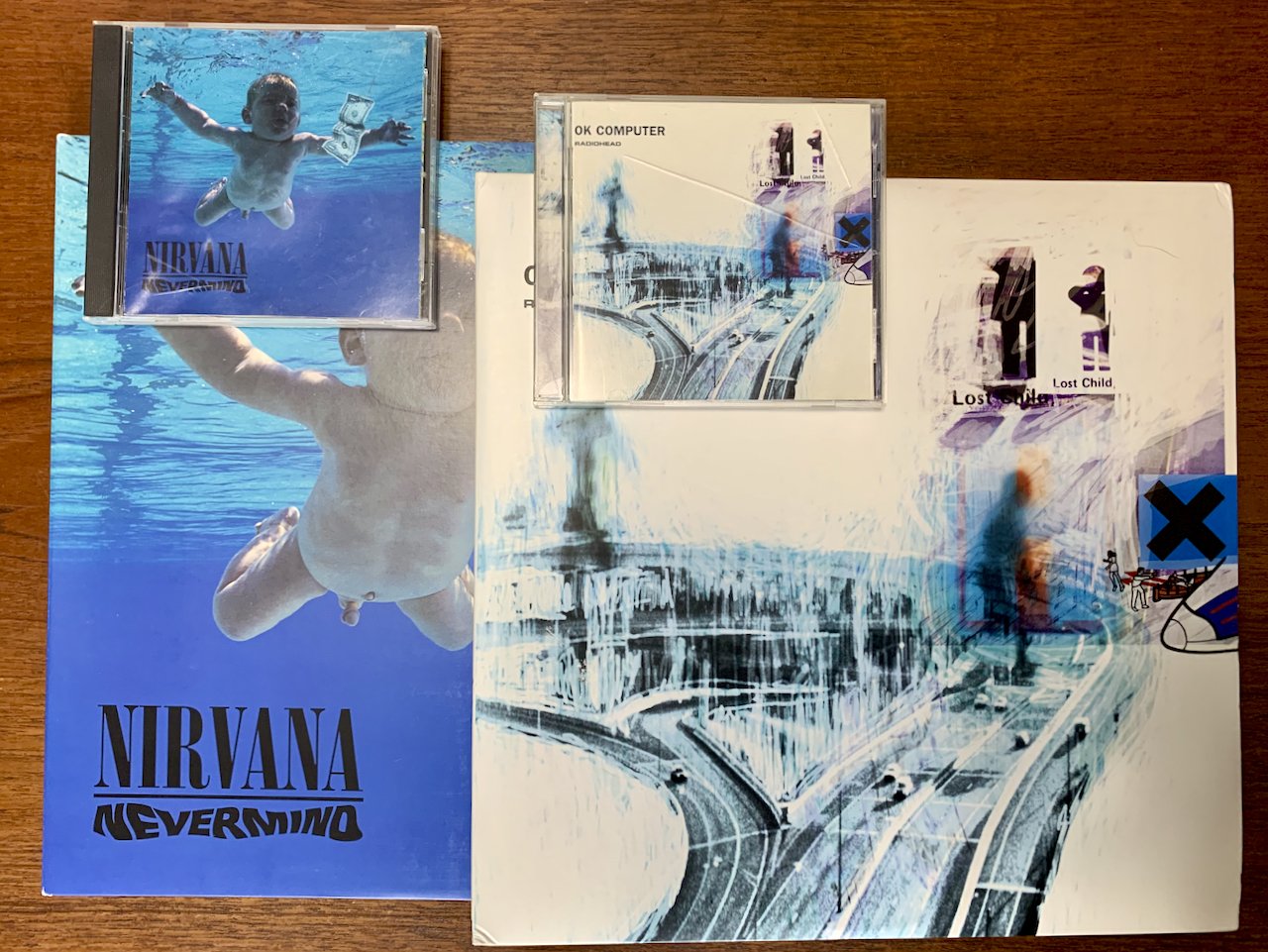

Music over the decades. From L to R, top to bottom: “Birth of the Cool” by Miles Davis (1949), “Ellington at Newport” by Duke Ellington (1956), “At Folsom Prison” by Johnny Cash (1968), “Abbey Road” by the Beatles (1969), “Blood on the Tracks” by Bob Dylan (1974), “Rumours” by Fleetwood Mac (1977), “Wish You Were Here” by Pink Floyd (1975), “Paul’s Boutique” by the Beastie Boys (1989), “Full Moon Fever” by Tom Petty (1989), “(What’s the Story) Morning Glory?” by Oasis (1995), “OK Computer” by Radiohead (1997), “The XX” by the XX (2009), and “Be the Cowboy” by Mitski (2018).

Aesthetic Reasons

(1) I prefer to own music. I used to believe that I would "own nothing and be happy." In fact, in a misguided attempt at minimalism, I aspired to transition everything in my life to the rental/subscription model. I now utterly reject this ethos. When it comes to music, I object for two reasons. First, subscribing to music means putting myself at the mercy of business decisions made by Apple and Amazon. (You may be on the end of a leash held by Spotify, or Google.) If, for example, an album I love ceases to be covered by a contract between label and streamer, it will disappear from the catalogue and I will no longer have the option to enjoy it. If a particular mix of an album I cherish is replaced by a "20th anniversary, deluxe, digitally re-mastered" version, the lowly original that I have come to love may no longer be available. (The problem is even more acute in video: entire scenes from beloved movies may be altered, if not eliminated, to make them more palatable politically, and the original may become unrecoverable. The case of "Han shot first" springs easily to mind.)

Second, I resent being subjected to onerous terms of service that I must swallow whole without protest. I especially resent the fact that the streamers retain the exclusive right to amend the terms without warning or consulting me and that the changes are inevitably made to benefit them, not me. I am powerless and un-free in this "relationship." By contrast, outright ownership gives me more rights over what is properly called my private property than I would have under a subscription model. I can, for example, make a back-up copy of the CD; I can lend it to a friend; I can trade it, sell it, or give it away. If I break up with my girlfriend, I can, in a thrilling act of catharsis, smash our make-out CD into a thousand tiny pieces to make the break-up complete and irreversible. Once I own a CD, it is mine; there is no need for me to continue to pay to enjoy it. My library of music does not vanish the moment I cancel my subscription, and I am shielded permanently from price hikes and inflation.

(2) I prefer physical over digital media. Of course, I freely acknowledge that the CD is "digital," but it is digital in physical form--and the physical form has to be put somewhere; it takes up space; it cannot be forgotten absolutely and permanently as can a digital file in the depths of nested folders on my hard drive, or a stream played long ago. A CD is a physical object that confronts the owner with a stark choice: it demands to be kept, or thrown away. If kept, where? How?

I organize my CDs alphabetically by artist. When I own multiple discs by the same artist, I sort them chronologically by date of album release. This makes my music easy to find and also gives me a straightforward way to remember whether I already own a particular disc when I am out hunting for "new" music. (This becomes a real problem when your library grows as large as mine has. I don't go so far as to keep a database, though I probably should, so that I can pull it up on my phone wherever I am.) I don't yet have a bespoke shelving solution. This is something I will investigate in the New Year.

I am not immune to the allure of minimalism and I recognize that my home could do with a deep de-cluttering. However, there are well-organized collections of objects that I choose to keep in the face of this recognition: books, CDs, records, and cameras. These objects, carefully arranged in my living and working spaces, serve as an external memory of who I was and am. They remind me of places, people, and periods in my life. When my memory grows dim, they insist: yes, this happened.

Music made for the compact disc—and for me.

(3) The CD was the dominant medium of music distribution in the 1990s when I came of age and began collecting in earnest. The CD is the musical medium of my youth. Albums like "Nevermind," "Ten," and "Siamese Dream" are forever associated with the CD in my mind; with trips on the bus from my university campus to A&B Sound on Seymour Street, where new releases could be had for $12; with late nights of studying in my dorm room as the six-dic changer atop my chest of drawers played at random; and with the music I borrowed and shared as my tastes expanded beyond the narrow confines of the 1980s alternative British scene (the Smiths, the Cure, and Depeche Mode.) Nirvana, Pearl Jam, Smashing Pumpkins, Faith No More -- this was the music that was made for the CD, not for vinyl, or for streaming. And it was the music that was made for me.

I have tried listening to music from this era on vinyl, but it just doesn’t sound right.

Philosophical Reasons

When I play a CD (or a record) I am spending 45 min absorbed in an entertaining experience that the algorithm knows nothing about. I am leaving no digital trace of my musical preferences, or indeed of my wider tastes in entertainment, and the algorithm learns nothing at all about me during that time. I am effectively limiting the surface area of my psychology available to attack by the AI. Does this make its future musical recommendations to me less accurate? Yes, undoubtedly. But that is a trade-off I am willing to make. I am willing to introduce inconvenience into my life for the sake of personal autonomy and privacy. I understand that the AI's primary objective is to make me more predictable, to reduce the range of my spontaneous, idiosyncratic, personal, and human choices, and therefore to transform me over time into a more perfect consumer. Whatever I can do, therefore, to thwart this objective, I should do. My local thrift store has become my algorithm; it's disorganized collection of discs bears no resemblance to the bespoke selection that Amazon sets before me. Instead of a carefully curated list, selected with uncanny accuracy specifically for me, I am confronted as I walk into the store with haphazard, picked-over piles of jewel cases--cases that every other customer sees; cases that are only accidentally overlapped with my preferences in music; cases that give me a window into the history of musical tastes of the people in my neighbourhood and remind me of my own historical relationship to music. These cases, which formerly resided in the living rooms and bedrooms of my community, give me a direct, physical connection to the culture of my time. Whatever I find while browsing the shelves is what I buy and listen to. This music satisfices. I allow myself to be guided by intuition and by a willingness to experiment when I select music, rather than being led by the nose like a dumb animal by the faceless algorithm which pretends to know me better than I know myself. And, given how inexpensive CDs have become, this is a low-cost activity. Indeed, the music itself is almost incidental. The experience of walking to the store, of talking with the owner, of browsing what's just arrived on the shelves, of anticipating what I might find--all of these things are an essential part of the musical journey for me. And, again, in all of these activities, I am leaving no data on which the AI can act. This is a deeply reactionary stance, which, though a very small step in the direction of resistance, I find to be necessary and satisfying.