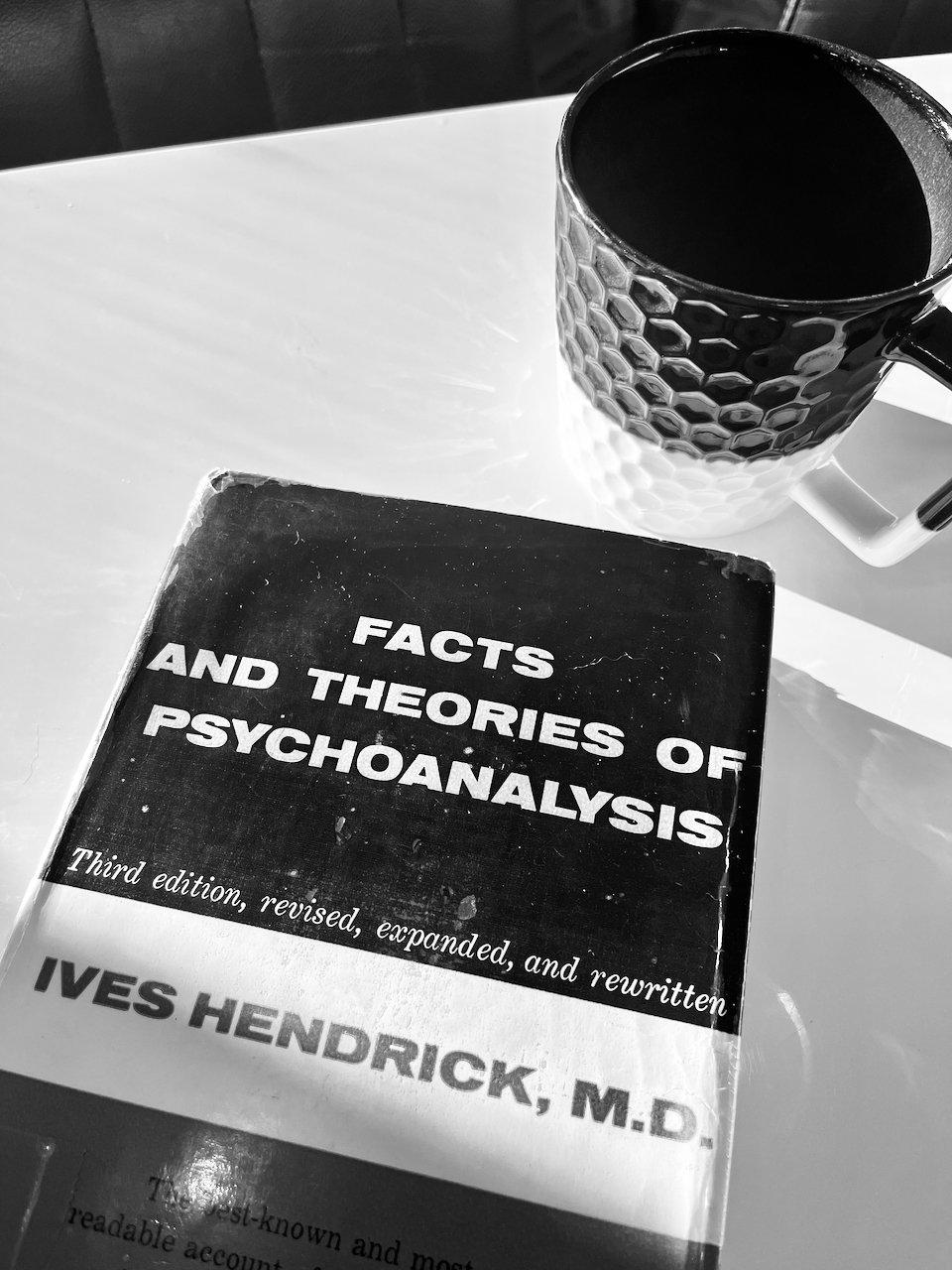

From the dust jacket

“A definitive statement of psychoanalytic theory and practice, the first to be written by an American psychoanalyst and, in the reviewer’s opinion, the best that has yet been written by any psychoanalyst” – Karl A. Menninger

A short biography of the author, Ives Hendrick, from the Boston Psychoanalytic Society and Institute:

Ives Hendrick (March 10, 1898 – May 28, 1972) was a psychiatrist and co-founder of the Boston Psychoanalytic Society and Institute. Born in New Haven, Connecticut to Burton and Bertha Hendrick, he was given the name “Ives” after his mother’s maiden name. In 1918 he entered Catholic University and then was admitted to Yale, where he studied pre-medical courses and went to medical school. Hendrick began his professional career as a medical service house-officer in New York at Lennox Hill Hospital under the chief resident, Carl Reich. By 1926, he had moved to Boston to work at the Boston Psychopathic Hospital. Soon Dr. Chapman of the Sheppard and Enoch Pratt hospital in Baltimore persuaded Hendrick to join the medical staff, so he moved again to Baltimore, MD, where he stayed from 1927 until 1928. In 1928 Hendrick traveled to Europe, and was analyzed by Dr. Alexander in Berlin. In the next two years he studied at the Berlin Psychoanalytic Institute. Hendrick returned to Boston in 1930, helped co-found the Boston Psychoanalytic Institute as a charter member and became its elected president (he returned to the presidential role at BPI from 1946 to 1947). At the same time he was also president of the American Psychoanalytic Association, joined the Harvard Medical School teaching staff, was an analyst at McLean hospital, and a consultant for the Massachusetts General Hospital. Besides countless articles and papers, Hendrick published three books: Facts and Theories (1934, 1939, 1958), Birth of an Institute (1961) about the Boston Psychoanalytic Institute, and Psychiatry Today (1964). Hendrick passed away of natural causes in 1972 and is buried in Evergreen Cemetary, New Haven, Connecticut.

And a brief review of the first edition of the book, from the Journal of the American Medical Association:

Although it is probable that psychoanalysis as a technic has come to stay, there still remain many questions about justifying the theories behind it. There are dissensions between members of the analytic and nonanalytic groups of psychiatrists and even some differences of interpretation and opinions among the freudian psychoanalysts themselves. Nevertheless, when those who have a proper background discuss psychoanalysis, they usually agree on the fundamentals. Much of the dissension has arisen from the lack of a good book on the basic theories and beliefs that are held by properly qualified psycho-analysts. The present volume is a compendium of psychoanalytic theories. There is little in it that is controversial and its facts are largely those presented by Freud himself rather than the products of some of his more bizarre disciples. The first part of the book presents the history of freudian psychology and the meaning of psychosexuality; the second part treats of the theories of psychoanalysis in which principles such as pleasure and reality are discussed. Aggressive behaviour toward parents is included here. Thirdly, there is a clear outline of psychoanalytic therapy, such associated phenomena as transference, also a discussion of treatment methods and the types of patients that are suitable for such treatment. The results of analysis are chiefly set forth, possibly with a little tendency to overvaluate some of them. The only part of the volume subject to criticism, and that only mild, is the fourth part, in which the author's view seems to be too rosy about the place of psychoanalysis and a little too condemnatory to other schools of psychotherapy. This work should be an excellent basic book for any one who wishes to understand psychoanalysis as it is presented today. It should supersede most of the older books devoted to the presentation of psychoanalysis for the beginner.

I have reproduced Hendrick’s excellent glossary on this website for those interested in psychoanalysis. I have found it to be a useful resource.