Leica R3

Version 1.0.1, January 4th, 2024, with corrections to technical aspects of the metering system based on reader feedback.

Ratings

The Camera

Build Quality and Design: ✭✭✭✭

Very well built, stripped down, no-nonsense design, limited ergonomics

Lens Compatibility and Quality: ✭✭✭½

Excellent optical quality, sturdy construction in lenses, limited availability of 3-cam versions, high prices

Viewfinder and Focussing System: ✭✭✭½

Large, bright viewfinder, though a step down from the Leicaflex SL2, limited information shown

Exposure Control and Metering: ✭✭✭½

Integrative and selective metering modes (no matrix), exposure compensation in full stops only

User Experience and Features: ✭✭✭½

Solid performer, though lingering questions about reliability; no shutter-priority auto-exposure; no auto-focus; no mirror lock-up

Pricing and Value for Money

Body only: $150–$300

Body and standard lens: $500–$800

Value for money: ✭✭✭

Introduction

Historical Roots of the Leica R3

Spurred by the rapid technological progress that took hold predominantly in post-WWII Japan, the camera market of the 1960s and 70s was characterized by intense competition and change. In these two decades, photographers came to prefer single-lens reflex (SLR) camera systems that were less expensive, smaller, lighter, and easier to use than older formats, while also offering the advantages of interchangeable lenses, motor drives, and other accessories that made them highly versatile and desirable by amateurs and professionals alike. The cameras of this period–produced primarily by the companies now known as Nikon, Canon, Pentax, and Minolta–also began to feature through-the-lens (TTL) metering systems and advanced electronics that enabled aperture-priority auto-exposure, which further contributed to their ease of use and popularity.

It was into this market that the storied German company Leitz (now Leica) introduced its first SLR camera in 1964. The Leicaflex, also known as the Leicaflex Standard, featured a horizontally-travelling, rubberized fabric shutter capable of speeds ranging from 1-1/2,000 s and a cadmium sulfide (CdS) light meter (though it did not make TTL measurements.) The camera introduced the Leica R-bayonet mount and was a direct competitor to the Nikon F, which had debuted in 1959. Market reception was disappointing. The camera’s complex construction and high quality components made it very expensive to produce and only 37,500 units, predominantly in chrome dressing, were ever made.

Nevertheless, Leitz was undeterred and, true to form, iterated the Leicaflex cautiously, even as it continued to develop its comparatively successful line of M-mount rangefinders: 1968 saw the introduction of the Leicaflex SL, which featured TTL spot metering (“SL” stood for “selective light”); 1972 greeted the Leicaflex SL “MOT” (the badge referring to the fact that the camera now allowed coupling of an optional, external motor drive for continuous, high-speed shooting); and, finally, 1974 welcomed the Leicaflex SL2, which further refined the features of the SL and bore the dubious honour of being so expensive to produce that each camera body had to be sold at a loss (in the hope that profit could be earned from the sale of lenses.)

None of these successor models was commercially successful. Worse still, Leitz could neither keep pace with the technical innovations that were rapidly diffusing into cameras manufactured in Japan, nor match the prices of its competitors in the Orient. In response to these challenges, Leitz entered into a cooperation agreement with Minolta in 1972. This partnership aimed to combine Leitz’s optical and mechanical engineering expertise with Minolta’s innovations in electronics. The first product of this collaboration was the Leica CL, a compact rangefinder camera introduced in 1973. However, the primary focus of the partnership was to develop a new line of SLR cameras that could compete effectively in the market.

The collaboration bore fruit with the release of the Minolta XE in 1974, which featured the advanced Leitz-Copal shutter. This camera set the stage for the development of the Leica R3, which was introduced in 1976. The R3 was designed to be a robust, feature-rich SLR that could leverage the strengths of both companies to meet the evolving demands of photographers.

Primary Features of the Leica R3

The Leica R3 stood out in the competitive SLR market of the mid-1970s due to several key features:

Electromechanical Shutter: The R3 featured an advanced electromechanical, vertically traveling, metallic, focal-plane shutter with speeds ranging from 1/1000 s to 4 s, and bulb (B). This shutter provided reliable and precise exposure control.

Dual Metering System: By way of a switch integrated with the shutter speed dial, the R3 offered both large-field integrating and selective (spot) metering modes that were based on three active (battery-powered) cadmium sulphide (CdS) photocells. The selective metering system covered approximately 7% of the viewfinder area ensuring accurate exposure of a the central subject. This flexibility allowed photographers to choose the most appropriate metering method based on the shooting conditions.

Aperture-Priority Auto-Exposure: The R3 supported aperture-priority auto-exposure mode, allowing photographers to set the aperture while the camera automatically selected the appropriate shutter speed. This feature made it quick and easy, even for inexperienced photographers, to achieve correct exposures in varying lighting conditions.

Build Quality: True to Leica’s reputation, the R3 was built with exceptional quality. It featured a sturdy, heavy chassis available in both all-black and black with chrome trim variants. The camera’s robust construction ensured durability and reliability, making it suitable for professional use.

Viewfinder: The R3’s viewfinder offered 92% frame coverage and 0.8x magnification, providing a bright and clear view for precise composition. The viewfinder included a needle indicating the camera’s calculated shutter speed and a windows indicating the selected aperture and exposure mode. Exposure compensation was not shown in the viewfinder.

Lens Compatibility: The R3 was fully compatible with Leica’s 3-cam and R-only lenses, which have been praised for their superior optical quality.

These features, combined with the expertise of both Leitz and Minolta, made the Leica R3 a formidable competitor in the SLR market. Primarily by establishing the foundation for a new generation of R-mount SLR cameras that featured electromechanical controls and auto-exposure modes, the R3 successfully addressed some of the shortcomings of its predecessors and positioned Leica as a serious contender in the evolving landscape of 35mm SLR photography.

Market Response

Despite these good features, the Leica R3 received a mixed response from photographers when it was released in 1976.

Positive Reactions

Build Quality and Durability: Many photographers appreciated the robust construction and high build quality of the R3, which was consistent with Leica’s reputation. The camera’s solid, metallic body and precise engineering were seen as major advantages, especially for professional use.

Advanced Features: The inclusion of aperture-priority auto-exposure was a significant draw. This feature made the R3 more versatile and user-friendly, appealing to photographers who wanted more automated control without sacrificing manual options.

Optical Quality: The compatibility with Leica’s renowned 3-cam and R-only lenses was a major selling point. Photographers valued the exceptional optical performance these lenses provided, which was a hallmark of Leica’s legacy.

Metering System: The dual metering system, offering both large-field integrating and selective light measurement, was praised for its flexibility and accuracy. This allowed photographers to achieve precise exposures in a variety of lighting conditions.

Criticisms

Weight and Size: Some photographers found the R3 to be relatively heavy and bulky compared to other SLRs available at the time. This made it less appealing for those who prioritized portability and ease of handling.

Complexity and Learning Curve: The advanced features and controls, while beneficial, also meant that the R3 had a steeper learning curve. Photographers who were used to simpler, fully mechanical cameras sometimes found the R3’s electronic systems and controls more challenging to master.

Battery Dependency: The reliance on batteries for the metering system and auto-exposure functions was a point of concern. Photographers worried about the potential for battery failure, which could render some of the camera’s key features inoperative.

Overall Sentiment

Despite some criticisms, the Leica R3 was generally well-regarded for its build quality, advanced features, and optical performance. It was seen as a significant step forward for Leica in the SLR market, combining the best of German optical engineering with Japanese electronic innovation. The camera appealed particularly to professional photographers and serious amateurs who valued precision and reliability in their equipment.

Comparison to the Leicaflex SL2

While sharing the R-mount, the Leica R3 and the Leicaflex SL2 represent two different eras of Leica’s SLR development. The SL2, introduced in 1974, was the last fully mechanical SLR produced by Leica alone and earned a well justified reputation for its exceptional build quality and precision. (The Leica R6 and R6.2, introduced in and , respectively, were fully mechanical SLR cameras that sprung from the Leica’s partnership with Minolta.) The SL2 featured a robust, all-metal construction and a large, bright, informative viewfinder with 100% frame coverage. The SL2’s horizontally-travelling mechanical shutter was highly reliable, offering speeds from 1-1/2,000 s and bulb.

Comparison of the Leica R3 (1976) to the Leicaflex SL2 (1974). These two cameras are very similar in physical dimensions and mass.

In contrast, the R3 embraced the emerging trend of electronic controls, incorporating an electromechanical shutter and aperture-priority auto-exposure. If Leitz included among its goals for the R3 to make it lighter and more compact than the SL2, the company failed to achieve them. Judged by my kitchen scale, the R3 weighs 785 g while the SL2 is slightly lighter at 777 g (batteries, body caps, and Peak Design strap lugs included for both cameras). There is a perception that the R3 did not quite match the SL2’s tank-like durability, but this may be generally true of comparisons between mechanical and electro-mechanical cameras, particularly when early versions of the latter are considered. However, the R3’s advanced features, such as aperture-priority auto-exposure, made it more versatile than the SL2 for various shooting conditions.

The SL2 was not compatible with Leica’s “R only” lenses. In addition, the R3 did not offer aperture-priority auto-exposure with the earlier single- and double-cam R lenses because these did not communicate the selected aperture to the camera body.

Comparison to the Minolta XE

As a result of the collaboration between Leitz and Minolta, the R3 and the XE overlapped significantly in their design and technology, though they were manufactured and released independently and asynchronously. The XE (also known as the XE-7 in the United States and the XE-1 in Europe) pre-dated the R3 by two years.

Comparison of the Leica R3 (1976) to the Minolta XE-1 (1974). These cameras share many aspects of design and technology.

Both cameras featured the Leitz-Copal electromechanical shutter giving speeds of 4 s to 1/1,000 s and bulb, and both offered TTL metering with aperture-priority auto-exposure. The metering systems were different, however. The XE incorporated Minolta’s Contrast Light Compensation (CLC) system, which was purported to deliver accurate exposure in high-contrast situations, such as a subject standing on dark terrain against a bright sky. The R3’s metering system, by contrast, was developed exclusively by Leica and afforded both “average” and “spot” options, selectable by a switch integrated with the shutter speed dial (and described in more detail below).

The R3 and the XE shared a chassis design, which meant that their physical dimensions were identical. However, they had different lens mounts and were distinguished by some minor features of fit and finish. Generally speaking, the Leica was considered to be superior to the Minolta in construction and refinement, though in my experience, the two cameras feel very much the same.

The Minolta XE

The Minolta XE (1974) is a wonderful, inexpensive, picture-making machine.

Layout

The placement of dials and levers was traditional in the R3: the left-hand side of the top plate of the camera (with lens facing away from the photographer) featured a combination ASA-exposure compensation collar surrounding the film rewind crank (both having locks to prevent inadvertent movement), while the right-hand side featured the shutter speed selection dial (including B, X, and AUTO settings), a threaded shutter-release button, and plastic-tipped film-advance crank coupled with double-exposure switch. The rear face of the camera featured a viewfinder blind lever and an on-off switch, as well as a window that showed both the frame counter and film-advance confirmation. The images below show these features in detail. (Click, or tap, to enlarge.)

Features

Metering. Designed to provide accurate exposures under a variety of lighting conditions, the R3’s metering system was one of its standout features. The camera offered two distinct metering modes: large-field integrating metering and selective light metering. This flexibility allowed photographers to choose the mode best suited to the shooting conditions and the subject matter. The sensitivity of the meter could be set from ASA 12 to 3200. The R3 lacked automatic DX decoding.

Large-field Integrating Mode. In this mode, by way of two photocells mounted above the pentaprism, the R3 measured the light reflected from the entire field of view, providing an average reading that took into account the overall brightness of the scene. It was well suited to evenly-lit scenes and was ideal for landscape photography and general-purpose shooting where the lighting was consistent across the frame. This mode prioritized “balance” in the exposure and worked to prevent over- or underexposure in large areas of the image.

Selective Light Mode. The selective light measurement system was enabled by a single photocell mounted in the base of the camera. It covered approximately 7% of the viewfinder area, centred on the focusing screen’s split-image rangefinder and microprism collar. This small coverage allowed precise exposure control, which was especially useful in high-contrast lighting situations. It was particularly effective for portrait photography and other scenarios where the subject was centrally located. By restricting the metering to the central area, the R3 ensured that the main subject was correctly exposed, even if the background was significantly brighter or darker.

Exposure Modes. The R3 offered both manual exposure and aperture-priority auto-exposure modes.

Manual Mode. In manual mode, the photographer set both the aperture and shutter speed, while the metering system (in either integrating or selective mode) provided a guide for the correct exposure by way of a vertically travelling needle on the right-hand side of the viewfinder.

Aperture-Priority Mode: In aperture-priority mode, the photographer selected the aperture, and the camera automatically set the appropriate shutter speed (steplessly) based on the meter reading.

Exposure Compensation. The R3 offered exposure compensation of +/- 2 stops in full stop increments.

Flash Compatibility and Synchronization. The R3 offered both “M” (bulb) and “X” (electronic) flash synchronization. “M”-synchronization speed depended on the nature the bulb used; it could be as slow as 1/30 s and as fast as 1/1000 s. “X”-synchronization was 1/90 s and could be used when the camera was set at any shutter speed between 4 s and 1/60 s, or bulb. Electronic flash units could be connected to the R3 either through the hot shoe on top located on top of the pentaprism, or by the cable contact marked “X” at the 3 o’clock position of the lens mount. Flash bulbs were fired by cable connection only (to the second contact marked “M”).

Self-timer. The R3 featured a 10 s delayed release system that was activated by (i) cocking the shutter; (ii) turning the self-timer lever, located on the front face of the camera, counter-clockwise; and (iii) pushing the revealed release button (formerly hidden behind the lever). The camera made a pronounced whirring noise while the lever smoothly returned to the 12 o’clock position, and the shutter fired just before the lever came to a halt.

Viewfinder and focussing. The R3’s viewfinder (shown schematically below) was large and bright. It covered 92% of the frame and had 0.8x magnification. It featured a central split-ring rangefinder with microprism collar set into ground glass. This combination made accurate focussing quite straightforward under most conditions. The current aperture was conveyed to the viewfinder optically via a small window pointing down towards the lens. The viewfinder also included a needle indicating the camera’s calculated shutter speed and windows showing both the selected aperture and either exposure mode (B, X, or A) or selected shutter speed. Exposure compensation was not shown in the viewfinder.

Example view through the viewfinder of the Leica R3, taken from the user manual. The readout at the top indicates that the camera has been set to f/4 and is in aperture-priority auto-exposure mode (A). The needle scale at the right-hand side indicates that the camera has selected a shutter speed somewhere between 1/60 s and 1/125 s. Note that shutter speed is varied steplessly when the camera is in A mode. The central circle contains the split-image rangefinder. When the top and bottom semicircles are aligned, as in this case, the image is in focus. Surrounding the split-image is a microprism collar to aid in focussing. When this appears to be fuzzy, the image is not properly focussed. Note that neither metering mode (integrating or spot) nor exposure compensation is shown in the viewfinder.

Lens Compatibility. The Leica R3 was fully compatible with 3-cam and R-only lenses featuring the Leica R bayonet mount. The chart below, taken from Wikipedia, illustrates the compatibility matrix between R-lens types and camera bodies. R-only lenses were deliberately designed by Leica to be incompatible with earlier Leicaflex cameras, and ROM lenses featured contacts for electronic communication between lens and camera.

Prime R-mount lenses are available in focal lengths ranging from wide to telephoto. Generally speaking, their optical performance is superb, as one would expect from Leica glass. Zoom lenses are also available, but these are inferior. Because the 3-cam lenses offer the widest compatibility, they are also the most desirable and command high prices on the used market. Another driver of the increasing prices for these superb lenses is their adaptability to a broad range of digital cameras. They can also be modified (“de-clicked”) for use in video.

Aesthetics, Handling, and Real-world Use

Like the Nikon FM- and FE-series of cameras, and the Leicaflex SL2 before it, the Leica R3 makes little allowance for ergonomics beyond rounded corners. The camera has no grip; its lines are straight and its aesthetics are boxy. This is offset by the solidity and heft of the camera, which conveys a confident, balanced feeling in the hand. Though it is heavy, the R3 positively wants to be picked up.

The R3 was designed for operation with two silver oxide batteries providing 1.55 V each. I use two LR44 alkaline batteries (rated at 1.50 V) in my camera. Possibly because of the lower total voltage supplied by these batteries compared to specifications (3.00 V vs. 3.10 V), or possibly because of the age of the silicon photodiode and associated electronics, my R3 tends to read the scene as being one stop too dim (as judged by comparison to other more modern cameras in my collection.) Therefore, I dial in a permanent +1 exposure compensation. I have obtained decent exposures with this compensation when using the camera in aperture-priority automatic mode with large-field integrative metering.

The R3 has a slotted collar on the take-up spool to make film loading more reliable. I found this to be a little finicky at first, but came to like and appreciate it over time. I am now confident that the film transport system will always engage properly on the first try. I can usually achieve 38 exposures (and sometimes 39!) on a 36 exposure roll; autoexposure modes are available even before the frame counter reads “1”. In the Nikon F3, by comparison, autoexposure is not active until the first official frame.

The shutter speed selection dial and integrated exposure mode switch are well placed and give positive haptic feedback. The double exposure switch is located at the 12 o’clock position under the film advance lever. In the default position, a single white dot is visible underneath; when the switch is thrown to the right, two dots are revealed to show that double exposure is now active. This “revealed state” is a clever touch, and carries over into the exposure mode switch: when it is in the right-hand position, a small, white rectangle is revealed to demonstrate that the meter is set to large-field integrating mode; when it is in the left hand position, this rectangle is hidden under the switch and a white dot is revealed to indicate that the meter is now in “spot” mode.

On the rear of the camera, there is an ON-OFF switch to the right of the viewfinder. I find this to be quite slow and difficult to turn, but nevertheless preferable to Nikon’s implementation, which uses the film advance lever to unlock the shutter release and turn on the light meter. When shooting the R3, the film advance lever can remain flush with the camera body while the shutter release button is depressed. In the Nikon FM and FE cameras, by comparison, the lever needs to be in the stand-off position (at a 30 degree angle to the body) for a photo to be taken, which means that it may poke you in the right eye when the camera is held in landscape orientation, or in the forehead when it is held in portrait orientation. It is a welcome relief not to have to deal with this annoyance when using the R3. However, it is always possible to forget to turn the camera off when not in use and thereby to deplete the batteries unnecessarily.

The action of the film-advance is smooth, silent, and satisfying—though not as good as that of the Nikon F3, which has the most buttery film advance I have ever experienced.

Reliability

A question commonly posed on Leica forums regarding the R-series is, “How reliable are these cameras?” The answers are mixed. Some people have experienced decades of faultless service from their bodies, while others complain that the electronic systems integral to the R3–R7 line are prone to failing and, when they inevitably fail, typically cannot be repaired. I have not yet experienced any trouble with my R3, but my R7, which contains more electronics, has been flaky. I urge you to be cautious when purchasing any R-series camera and do your due diligence in making sure that it works before investing.

Pros and Cons

PROS

Pleasing aesthetics, with excellent build quality. Good sense of balance in the hand. Well-considered layout of controls with good haptic feedback and locks to prevent inadvertent modification.

Reliable metering system, switchable between integrating and spot modes, that produces good exposures in most lighting conditions. I find that I can safely depend upon aperture-priority auto-exposure most of the time.

Large, bright viewfinder with good coverage and reasonable magnification. Excellent information presented in the viewfinder in a legible, non-distracting way.

Wide range of available lenses which have outstanding optical performance.

Reliable film loading system, with film advance confirmation window.

CONS

The R3 was the first of Leica’s cameras to feature auto-exposure. Its electronic systems are now almost 50 years old and may be prone to failure.

Although the Leica R3 body may be had at a reasonable price (compared to comparable M bodies, like the M3), three-cam R lenses are expensive because they are desirable for their outstanding optical performance outside the Leica R ecosystem: they can be adapted to digital cameras of many brands and modified for video. So, they have appreciated on the used market.

Bulky and heavy. Neither smaller nor lighter than the Leicaflex SL2.

Buying Advice

I came to purchase the R3 because I am actively interested in the history of Leica SLR cameras. Prior to owning the R3, I had for more than two years been an active shooter of the almost perfect Leica R7 and, more recently, of the Minolta XE-1 and XE-5. My own interest in the camera is therefore idiosyncratic and combines making photographs with collecting cameras and pursuing a particular kind of technological archaeology. This may not reflect your own curiosity in the R3, that is, the R3 may not be an appropriate candidate for the job that you are hiring a camera to do. If are motivated predominantly by making (film) photographs, and especially if you are relatively new to the hobby, the R3 may not be the tool for you. I don’t make this claim from an exclusionary/elitist standpoint (as some Leica aficionados do); there are merely many better (cheaper, more reliable, lighter) cameras out there that are moreover well supported by large ecosystems of affordable lenses, accessories, spare parts, and service. The Nikon FE and FE2 spring easily to mind. I would not hesitate to recommend either of those cameras over the R3 as everyday picture-making machines.

That being said, if you want a comparatively low-cost entry into the Leica brand and aesthetic, the R-system SLR cameras are a good option (particularly if the rangefinder does not agree with you.) Bear in mind the following two important points when taking this road, however:

The electronics in the R-series of cameras may be prone to failure and cannot be repaired.

The R-mount lenses are expensive.

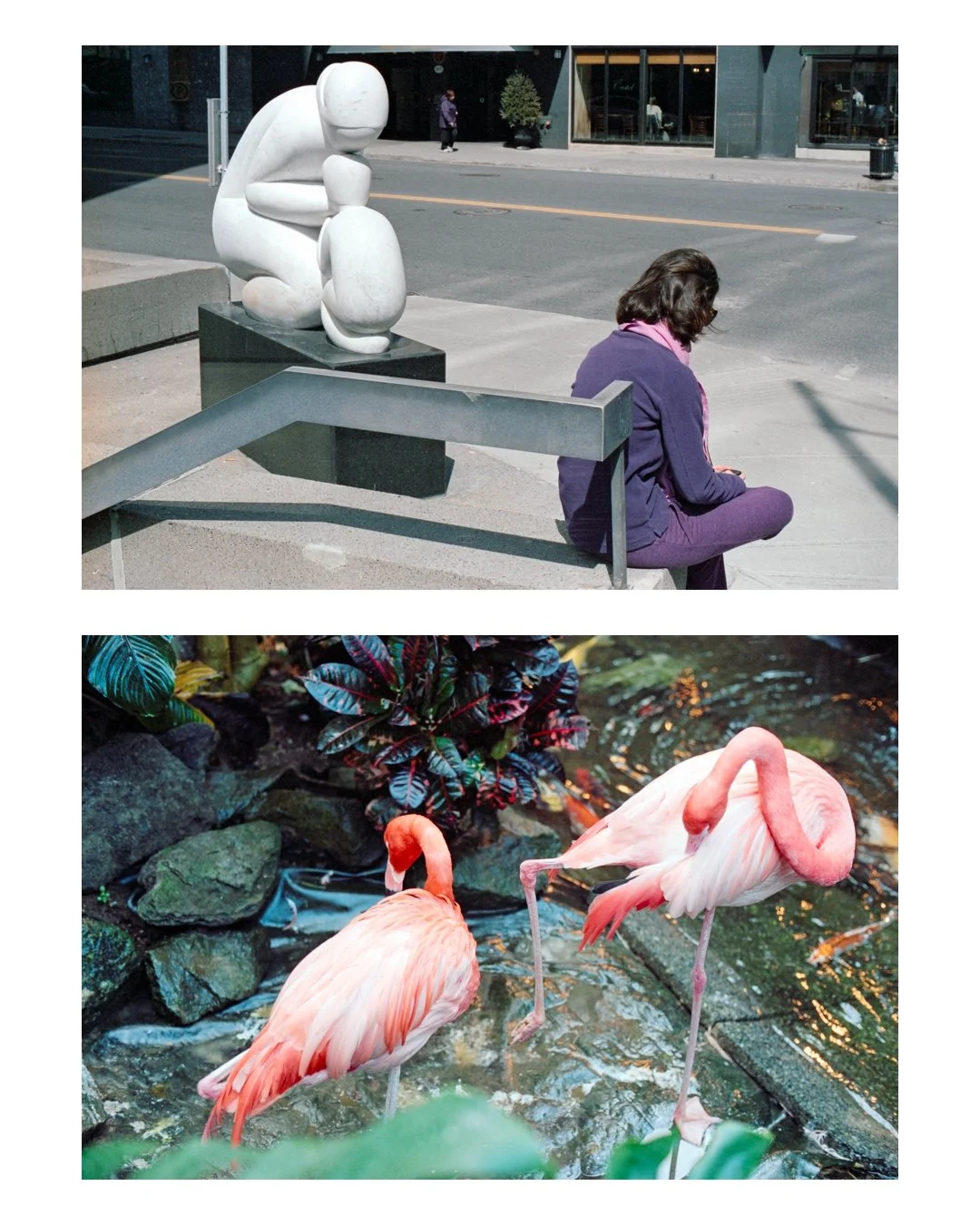

Sample Photos

Other Resources

Other Camera Reviews

Since 2023, I have been working to review all of the cameras that I own and use. This is a large project because my collection contains approximately two dozen cameras spanning 5 brands. For a complete list of my cameras and the current status of the project, see Completed and Upcoming Film Camera Reviews.